Winner, Winner Chicken Dinner

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics has released its Consumer Price Index for December 2019. Year-over-year CPI-U inflation came in at 2.29 percent for the month, nearly 30 basis points above the Federal Reserve’s stated 2 percent target. It has averaged just 1.55 percent since February 2013, reaching a low of -0.24 percent in January 2015 and a high of 2.95 percent in July 2018.

That might not mean much to you, but it means a lot to me. It marks the end of a nearly seven-year bet with my dissertation advisor — a bet that I have officially won.

In a February 2013 Washington Post article, Ylan Q. Mui quoted Lawrence H. White characterizing a Virginia Commonwealth resolution to consider issuing its own money as a “state-level expression of concern about the uncharted course the Federal Reserve has been on in monetary policy.”

No surprise there. The Fed had completed two rounds of quantitative easing (QE), seeing its balance sheet expand from $925 billion in September 2008 to $2,925 billion in February 2012; and, in September 2012, it had announced it would soon begin a third round of QE. The expansion was unprecedented, not merely because it was so large but also because it involved purchasing much riskier assets, including mortgage-backed securities. And, considering that Larry is a longtime Fed critic, it seemed natural that he would call attention to such policies.

What surprised me was Mui’s description of his inflation forecast. “White doesn’t subscribe to the doomsday scenario,” she wrote, “but he’s no optimist, either. He predicted that the inflation rate would rise to 5 percent before the end of the decade and eventually reach 10 percent.”

Really? Double-digit inflation? That seemed unlikely to me. Perhaps the Fed had raised the risk of inflation by expanding its balance sheet with unconventional asset purchases. But, if inflation picked up, it could sell those assets. And, if at that time it found its assets were worth less than what it had paid for them, it could use its new tool of paying interest on reserves to keep inflation from getting out of hand.

I wasn’t alone. Markets were also predicting relatively low inflation at the time. The 10-year TIPS spread, which is calculated by subtracting the interest rate on 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) from that on traditional 10-year Treasuries and provides a reasonable estimate of annual inflation expectations over the same time horizon, stood at just 2.5 percent.

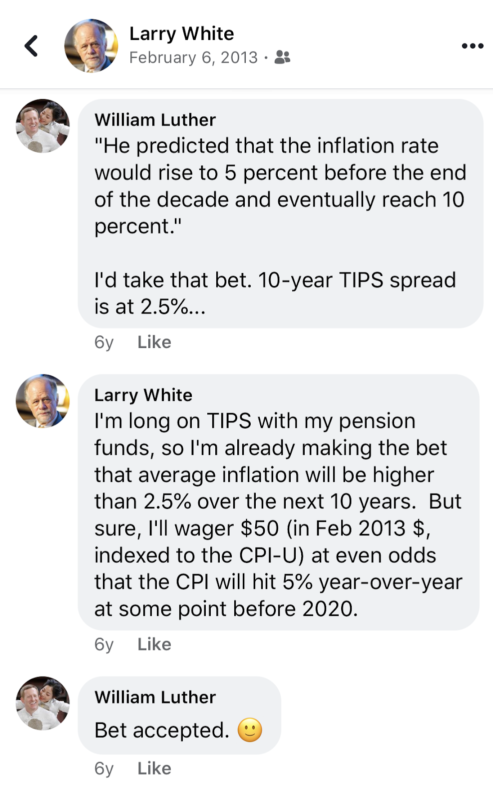

Surprised that my dissertation advisor, who taught me most of what I know about monetary economics, held such a radical forecast of inflation and emboldened by the discovery that market participants were much closer to my view than his, I did what any self-respecting economist would do: I proposed a bet. Larry clarified the terms: $50 (in February 2013 dollars, indexed to CPI-U) at even odds that the year-over-year CPI-U inflation rate would hit 5 percent or higher before 2020. And, with a virtual handshake, the waiting began.

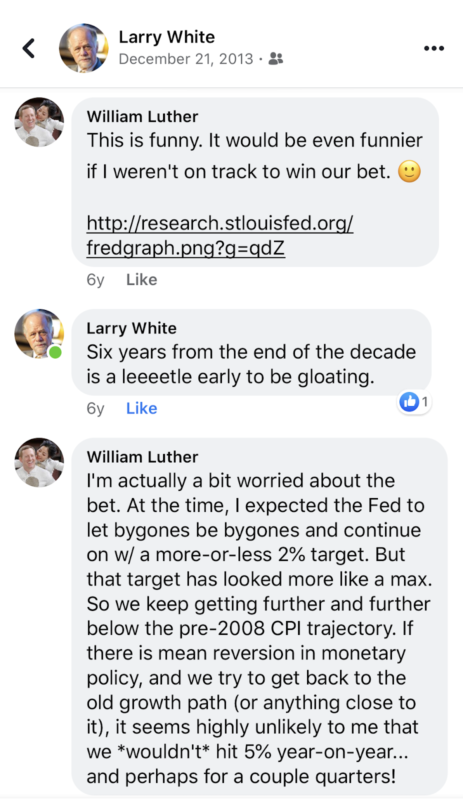

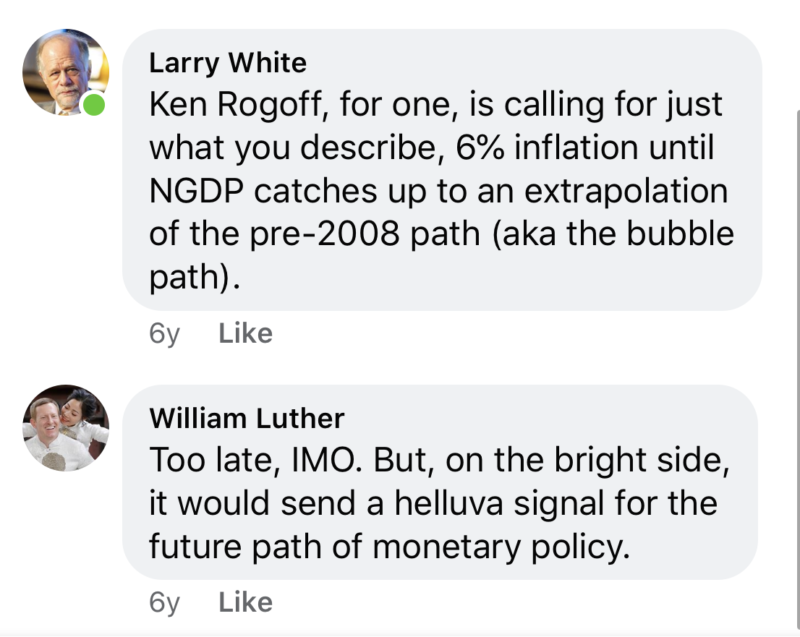

I will be honest: There were times when I thought I would lose this bet. Sure, inflation remained low over the period — even lower than the Fed’s 2 percent target. But inflation had been so low that some economists, including Harvard’s Ken Rogoff, were recommending temporarily higher rates of inflation in order to catch up with the old price level or nominal income trajectories. Any effort to catch up would require much more than 2 percent inflation. Rogoff was recommending 6 percent.

Fortunately for me, the Fed continued to let bygones be bygones. If anything, it treated its 2 percent target more like a ceiling than a symmetric target. This has led many economists, including the Mercatus Center’s David Beckworth, to claim monetary policy has been “too tight,” resulting in a slower recovery than was necessary.

Reasonable people can disagree with respect to whether the low inflation realized over the last decade amounts to tight monetary policy. (For what it’s worth, I say no.)

But one thing is beyond debate: Larry White owes me $55.49.