An Answer to That Viral Equality Meme

Concern over inequality and its consequences are all the rage these days, and it usually results in calls for some central authority to provide greater equity via coercive mandates such as tax policy or minimum wage laws. But can the free market help sort out some of these consequences in a manner that provides greater well-being for all involved?

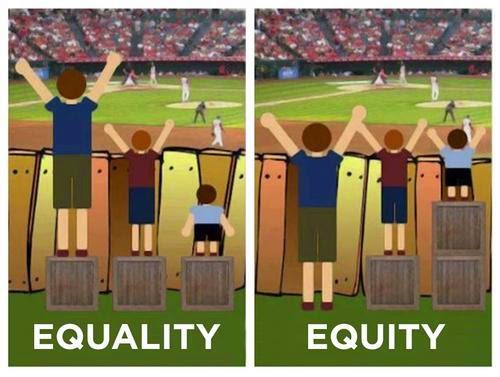

Not long ago, during a classroom discussion on inequality, a student brought to my attention a popular meme that had been making the rounds on the Internet. The graphic presents two pictures of three individuals of varying heights trying to watch a baseball game over a fence.

In the picture represented by “equality,” the individuals are standing on boxes of similar heights but only two people can see the game. The implication is that “equality of condition” is unfair to some.

The next drawing, subtitled “equity,” shows the shortest person given an additional box (implicitly taken from the tallest person) so that all people can view the game equally. Equity implies a redistribution of original circumstances to create equitable, and supposedly “fair,” outcomes. While this redistribution may have come voluntarily, the argument usually attached to this graphic (and the one made by my student) was that government is needed to realize more equitable outcomes taking something (boxes or income) from people who have “too much” and giving it to those who do not “have enough.”

But the first thing that struck me about this graphic, and which I pointed out to my student, is that the problem was visibly solved by the free market. The background of the photo features a baseball stadium with tiered seating! In order to attract a large audience, the owners of the venue designed a stadium with rows of seats that would allow people to see over one another.* Non-tiered seating would guarantee a smaller audience, especially if tall people took up the front row. The goal of the venue operator is to make as many people happy as possible so they keep coming back and tell others how good the game is.

My student was quick on the uptake, though, and noted that only “rich people” could afford to pay the entrance fee to get into the stadium. A fair point, until I pointed out two things. First, most venues offer different price points for tickets based upon the value of the seats. While it may be true that only “rich folks” can afford the box seats in the front row, there may be some lower income folks who really, really like baseball and are willing to splurge every so often. Beyond that, though, many stadium owners offer cheaper seats and discounts to individuals who might not want (or cannot) spend too much. Group discounts for families, Little League Teams, inner city youth programs, are par for the course because the owners know that income is not static and someday these “poor” consumers might be in a position to purchase the pricier tickets.

But second, and more importantly, if the owner of the venue didn’t charge an admission price to “rich folks,” there would not likely be a high-quality game to watch. The players, who have opportunity costs, will demand to be compensated for their time playing (as compared to being truck drivers or physical therapists).

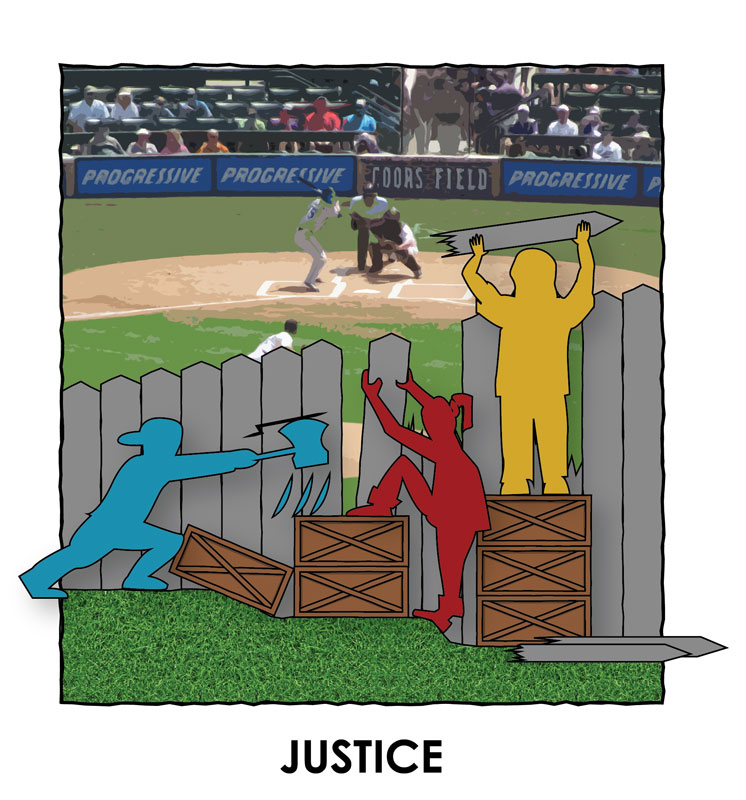

A second graphic that accompanies the “equality-equity” meme is one wherein the folks who are standing outside the stadium actually tear down the fence in an “act of liberation” (see below).

Alas, if there wasn’t some degree of exclusion and nobody paid an entrance fee, it would be unlikely that any high-quality players would want to play the game. Nobody would be able to watch!

There is an additional, delicious irony to the “liberation” meme. Looking closely, the stadium where the fence is being torn down has advertising from large corporations like Progressive Insurance and Coors. The ability of the venue to sell advertising in (or naming rights to) the stadium helps keep ticket prices lower for individual fans while paying higher-quality players to play.

Free markets come to the rescue once again! Markets, paradoxically, are naturally inclusive because of the ability to exclude on price margins. If you can reliably capture revenue via exclusionary pricing, you can find innovative ways to expand the market by lowering prices to more and more consumers. This is one of the reasons fans who can’t afford to make it to the ballpark can watch the game on television or listen on the radio at a substantially lower cost. Why stand uncomfortably on a box when Major League Baseball will let you “look over the fence” from your own couch.**

Free market capitalism naturally seeks ways to be inclusive by trying to attract a wider consumer base. Minor league and semi-professional leagues offer opportunities to see a game similar to a MLB one, but at a lower price. Granted, the quality of the game may not be as high, but the “fence” (i.e., price) is a bit lower. Market systems might not allow everyone to drive the Ferrari they want, but it does allow a lot of people to drive cars nonetheless, a luxury which only the elite could afford a few generations ago. And those who cannot afford to own a car (or choose not to) still can enjoy the advantages of faster transportation by way of rental car agencies, taxis, or Uber. Like discounted baseball tickets and minor league games, all of these innovations represent ways in which markets promoted more equitable access to the luxuries of life.

The important point here is that students who are critical of capitalism often overlook one of the most potent engines of equality in human history – free markets and the incentive to find innovative ways to please consumers! Sometimes the answer is in plain sight and as easy to see as a low hanging curve right over home plate.

— Footnotes —

*In contemporary times, it is true that large sports stadiums are funded out of the public coffers, an unfortunate side-effect of political rent-seeking. Nonetheless, these public stadiums would not be conceivable if there weren’t private entities like Major League Baseball that see an opportunity for connecting to a broad market.

**My students will often ask, “But what if the person can’t afford a television, radio, sofa, or even a house?!” If that is the case, I respond, then being able to see a baseball game is the least of their concerns. Fortunately, we live in a country and at a time where such situations are increasingly rare.