Coffee Robots are Not Causing Homeless People to Starve

A couple of months ago, this tweet made the social media rounds:

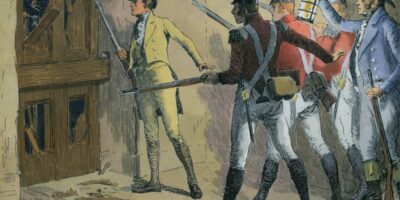

San Francisco in one photo.

Fully Robotic Coffeeshop next to the Starving Jobless Homeless pic.twitter.com/uwK936Twb5

— ERIK FIN (@erikfinman) January 14, 2019

The group of “Starving Jobless Homeless” people huddled outdoors next to a “Fully Robotic Coffeeshop” is jarring. The coffee shop, CafeX, features “Coffee from the best local roasters crafted with precision using recipes designed by top baristas.” It’s an image of the coming techno-dystopia in which robots take our jobs and leave everyone who isn’t a capital-owning plutocrat to starve in the streets, no?

No. There are other things at play here. One reply to the tweet tagged John Stossel and diagnosed the problem immediately: the minimum wage in San Francisco is $15 per hour. That is a wage at which, apparently, the people in the picture cannot be profitably employed and which induces firms to look harder for ways to do with capital what was formerly profitable to do with labor.

Labor and Capital

“But firms will want to innovate and adopt new technology no matter what,” you say. Maybe: it depends on what the technological possibilities are. If labor is extremely abundant, then the low-cost, most efficient production method might be labor-intensive rather than capital-intensive.

Think about why so many people don’t buy the absolute-best top-of-the-line computers or smartphones. You probably don’t. Consider the Cray XT5m supercomputer system, which “starts around $500,000, takes advantage of the hardware and software advances of the Cray XT5 supercomputer, the basis of the petascale system currently in use at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory.”

That’s a heck of a machine, and if you’re doing particle physics, it’s probably nice to have. If all you need to do is check your email and manage a few spreadsheets, then it’s overkill. Just as you wouldn’t expect a firm to buy a Cray XT5m for everyone in the office and just as you probably don’t keep one in the sewing room from which to check email and play Minecraft, firms aren’t going to go for hyper-tech when that tech is hyper-expensive.

Again, firms will choose the lowest-cost way to produce a good in the interest of maximizing profits. When we use legislation like minimum wages and workplace safety rules and other things to increase the price of labor relative to what would obtain in the free market, we nudge firms toward replacing people with machines — as CafeX does, replacing human baristas with mechanical ones.

That gives us the phenomenon in the picture: a mass of people who are either unemployed or who have given up on the labor market, huddled outside a robotic coffee bar.

The same principles also explain why they are without housing. First, building new housing in San Francisco is notoriously difficult. Reason discusses an amusing-if-it-weren’t-so-tragic case in which the owner of a laundromat is being blocked from turning it into an eight-story apartment complex because the laundromat is “historic.”

Making it difficult for people to build new housing reduces the supply of housing, which drives up prices. It also changes the composition of housing: high regulatory costs that make it hard to build any kind of housing will induce substitution away from modest housing and toward luxury housing.

Changes in Relative Prices

Economists call this the Alchian-Allen effect after the economists Armen Alchian and William Allen. Adding a fixed cost to two similar goods will induce substitution toward the higher-quality good because it changes the relative price of that good.

The average quality of oranges in Florida, for example, is lower than the average quality of oranges in Vancouver for this reason. Suppose good oranges have a price of a dollar and bad oranges have a price of 50 cents. This means good oranges cost two bad oranges; a bad orange costs half a good orange. If it costs 50 cents to ship an orange — any orange — from Florida to Vancouver, it changes the relative price. Good oranges are relatively cheaper: with a total cost of $1.50 including shipping compared to $1 for bad oranges, good oranges only cost 1.5 bad oranges. The relative price of bad oranges rises, from half a good orange to 2/3 of a good orange. (The numbers in this example are from an example in Steven Landsburg’s textbook Price Theory and Applications.)

People substitute toward higher-quality oranges and away from lower-quality ones. Before you say, “Wouldn’t people always buy the highest-quality oranges?,” note that there is a price difference. Then look in your own fridge or on your own kitchen counter. You probably don’t have the absolutely highest-quality produce imaginable on hand.

Now, replace good and bad oranges with luxury and modest apartments and replace the fixed cost of shipping with a fixed cost of building. Costly regulations make all housing absolutely more expensive, but they make luxury housing relatively cheaper.

If you’re still not convinced, think about hiring a babysitter for $40 and going on a date. Would you go to Taco Bell? Or would you go somewhere nicer? Adding the price of the babysitter means going to Taco Bell and spending $10 each would cost you $60. Or you could go to a very nice restaurant and spend $40 each for a total of $120.

Without the cost of the babysitter, a trip to the very nice restaurant costs you four trips to Taco Bell. But the trip to the very nice restaurant is cheaper in terms of forgone trips to Taco Bell once you add the cost of the babysitter, which will cost $40 no matter what you do.

As the San Francisco Tenants Union explains, “In San Francisco, most tenants are covered by rent control.” Rent control is a standard example in introductory economics classes of a policy that hurts the people we ostensibly want to help. The Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck has said that “in many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city — except for bombing.”

By holding prices below what the market will bear, rent-control ordinances ensure housing shortages, where, at the controlled price, people want more housing than firms and landlords are willing to provide.

Furthermore, they find themselves in a cat-and-mouse game with regulators because landlords and tenants move toward competition on non-price margins. Quality, to use just one example, falls because of rent control and necessitates, in the eyes of many activists, even more regulation.

The additional regulation raises the cost of providing housing, which reduces the supply of housing, which puts pressure on prices and thus leads to more and more calls for rent control. The outcome is grotesque: all the new construction is high-end luxury housing while the rent-controlled housing deteriorates more quickly.

Adam Smith famously wrote that “there is a great deal of ruin in a nation.” Does the picture of a huddled mass of homeless people outside a robotic coffee shop suggest the ruins of late-stage capitalism? I think not. It represents instead the “great deal of ruin” policymakers create when they make policy as if the laws of supply and demand are optional.