Don’t Blame Technology, Blame Yourself

An older woman and her middle-aged son were at a public restaurant for Thanksgiving. He spent the whole of the dinner flipping through his phone, without uttering a word. She did her best to maintain her dignity while looking past him and trying to pretend that this is what life is like. This tragic scene lasted until they paid the bill and left.

The scene was relayed to me by a senior in college who explains how her generation is figuring out the right and wrong ways to use new technology, correcting for the errors of their parents, who somehow allowed their lives to be drained by the newness of it all.

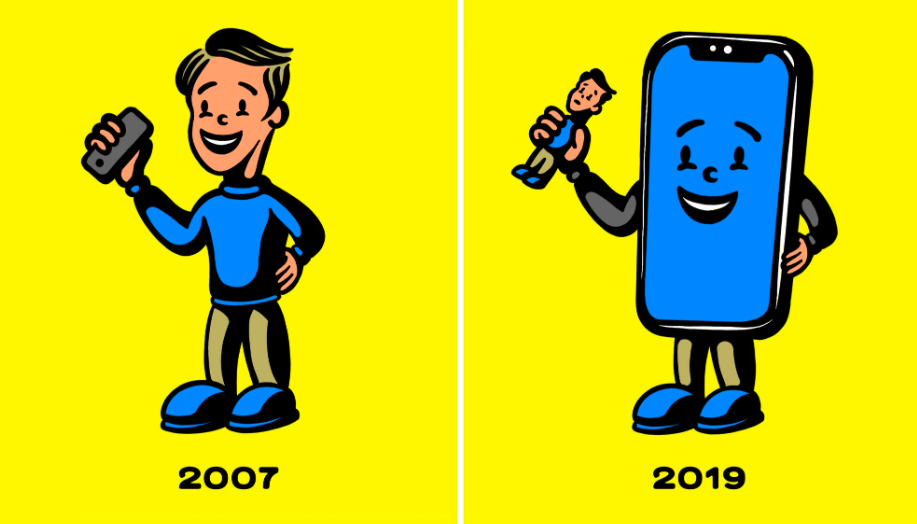

Zak Tebbal drew the perfect cartoon for how our relationship to our smartphones has changed over the last 10 years.

No one planned it. It just seemed to happen. The gadget scratched an itch. We have to know everything, to be in touch with everyone, to be everywhere at once. It’s an everything box, miraculous in its own way. Why are so many people creeped out these days that we seem to have turned over the whole of our lives to our smartphones?

It began with Facebook’s brilliant notification system. Your friends are contacting you, liking you, appreciating you, and surely you need to know that! Every application caught on. More buzzes, dings, alerts, reasons to stare and scroll. During this time, your device holds your primary attention, and interrupts anything else that is happening.

Hours and hours per day, adding up to a day or two in a week, a week in a month, and, ultimately, years and years of our lives, staring senselessly at things that matter maybe a little but not that much.

And at what cost? Disciplined reading, social engagement with those around us, our attention span, serious thought, and even our sleep. No one signed up for our lives to be put into total upheaval one step at a time, forsaking all human connection and conversation, and eschewing serious mental and emotional development, in favor of digital trivia 24/7. And yet, this is what it has come to.

And we are shocked to learn that all kinds of enterprises have an interest in what precisely we are doing. It’s the greatest marketing opportunity ever conceived, and we’ve tacitly approved of it all every step of the way.

Some users are starting to catch on. Now we are reading guides all over the internet on how to detox from our addictions. Back in 2011, I wrote a book called Beautiful Anarchy that celebrates the merits of all the platforms that many people now find oppressive, myself included. As a result, I’ve felt the need to come to terms with the change. Did I make a mistake? Why did I fail to anticipate how much of a burden it would all become?

The thesis of my book was not that we should allow digital platforms to rule our lives; it was that digital platforms aid in helping us curate a civilization for ourselves. It’s the curation part that has gone wrong. We just haven’t been very good at it. I’m confident that we’ll get there after fits and starts.

Is This Addiction?

I’m always suspicious of claims that we are addicted to this or that. Addiction sounds medical whereas what we are usually talking about comes down to bad habits. I had a bad habit of smoking. I did it for 30 years. Then one day something snapped. I didn’t want to be a smoker anymore. That was it, not even one more cigarette since that day. The human mind can overcome even biochemical urges.

Surely we can deal with information addiction so that we can regain control of our lives.

We are too quick to blame technology rather than ourselves. The apps we love specialize in getting our attention and drawing it away from other things. Good for them. This is their job, just as advertisers’ main job is to persuade us to buy the product. We don’t have to. If we are manipulated into feeding false wants, that’s not the advertiser’s fault; it is ours for going along as if we don’t really feel we have volition.

I’m thinking back to my childhood when I first developed a desire to have more stuff. I watched the ads incessantly on Saturday morning. I wanted everything: the Big Wheel, the Moon Boots, the Sit and Spin, Tonka Trucks, Sugar Smacks, Honey Comb, Hot Wheel Tracks, you name it. Every new toy had to be mine. I wanted every fun cereal. My parents bought me my favorite cereals and indulged my desires during the holiday season.

Then I gradually learned that this stuff was not all it was cracked up to be, and I gained control of the materially acquisitive part of my brain.

Which is to say: I matured. So too must we all with our digital devices.

Recall when cell phones first came out. It was like a miracle. We had our own phones rather than having to share the same phone in a household. No wires. We could talk to anyone from anywhere. Restaurants had early adopters sitting at tables alone yammering on the phone in a way that disturbed everyone around them.

It’s been years since I’ve seen such rude behavior. The court of taste and manners ruled against it. People have come to comply.

Now we have a different problem. We can’t get through a dinner with friends without half the guests checking their phones every few minutes. We have truncated conversations, stopping and starting because people can’t keep up with the line of thought. Tiny little buzzes are everywhere. You can see it in people’s eyes that they aren’t really there. They are thinking about their smartphones and applications.

This was happening to me, I admit. Then I entered into a social context in which constant smartphone checking was verboten. It took some discipline, but I eventually adapted, with happy results. If you absolutely must pull out the phone, it’s a simple matter of excusing yourself from the public space and then returning once your curiosity is satisfied. After a while, you realize that nothing is important enough to interrupt conversation with friends.

There still remained the problem of too many notifications. The fix was simple (once you figure it out), but it took active measures. I shut down several Slack channels. I deleted applications. Buzzfeed has no claim on my time. Neither does Wired. There is nothing on Snapchat that merits my immediate attention. Emails too can wait until a time convenient for me. I accepted only the most urgent ones, realizing that it is actually not important to know how many people are liking an Insta image.

With a few changes, I deleted 90 percent of my notifications and the constant buzzing came to an end. I got my life back rather easily actually.

Another way to put it is that I trained my device to act in accordance with a matured way of understanding its role. The providers of information services are trying to elicit from within me my seven-year-old inner self. I don’t fault them for that. It’s up to us to push back and behave like adults.

Economists have been arguing for a while about whether individuals make rational decisions or need nudges to make them behave in a way that is best for them in the long run. But there is a third option: we learn from mistakes and adapt our behavior in light of the consequences. We improve over time. Experience creates new principles and rules that we voluntarily adopt in our own best interest.

Every new technology comes with an awkward stage of adoption, during which time people get manipulated and break every kind of rule of propriety until they figure out a better way. This is where we are today. It’s not that the technology is failing us. It’s that we need to figure out how to become its master rather than the reverse.

The market forces that have put the whole of human knowledge in our pocket work best when we stop blaming technology and start taking responsibility for our own lives.