How a Strong Private Sector Will Address Climate Change

Though familiar with the current left flank of the Democratic Party’s capacity to think big, even I was surprised by the sketch of the Green New Deal laid out by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey in a draft resolution on Thursday. The first one-pager I saw through in the job guarantee and Medicare-for-all as sort of postscripts, bullet points at the end of a much bigger list.

While short on specifics, the resolution sets goals requiring government intervention in the economy at unprecedented levels. Advocates often invoke an existential threat, but my analysis below uses the exact same data as a jumping-off point. A world with a changing climate will desperately need a strong private sector.

The Same Deal

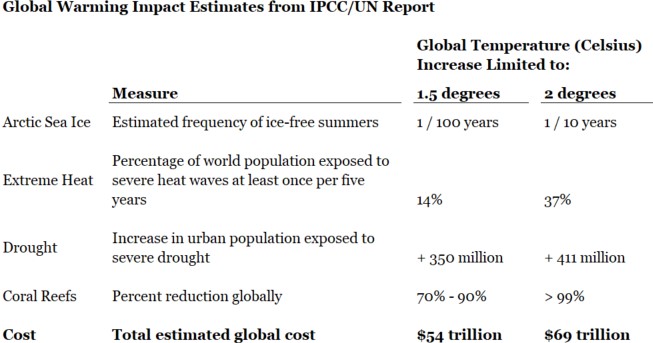

When I was first exploring the October 2018 UN reports that have become the benchmark for predictions of consequences of global warming for advocates of the Green New Deal, I made a table that I’ll reprint here:

The first column, if humankind limits total warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrialized levels, was the scientists’ estimate of what we face under even under the goals set out in the Green New Deal resolution. The second column, limiting to 2 degrees above pre-industrialized levels, is the likely result if countries keep their obligations under the Paris accords, which most currently aren’t doing.

The Green New Deal resolution lists similar consequences in the event we wind up “at or above 2 degree levels.” It does not list the consequences we will face at 1.5 degrees even if the world immediately enacts Green New Deals, saying only that “global temperatures must be kept below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrialized levels to avoid the most severe impacts of a changing climate,” with “most severe impacts” an adept escape clause. To an uninformed reader not parsing every word, this clearly sounds like the Green New Deal will zero out those impacts, rather than just moving us from the 2-degree to the 1.5-degree column.

In reality, the Green New Deal won’t fully accomplish even that goal. I previously wrote that “Frankly, the probability that the United States could design, pass, and fully implement legislation with a real impact by the target date of 2030 is almost zero.” (Thanks to our interns Micha Gartz and Callum Hudson for reminding me that “international cooperation” was a glaring omission from the quote.)

Finally, if there’s such an emergency, why include measures in the Green New Deal resolution, such as the job guarantee, that would be explosively controversial on their own and don’t appear directly tied to the goal of reducing emissions? The Green New Deal resolution appears at best to be an over-eager power-grab from the left.

A Challenge to Free Society

Anyone who believes that not enough has been done to mitigate the likely effects of climate change must believe that neither the government nor the private sector has passed any empirical test. The sorry state of the Green New Deal resolution underscores this point, rather than providing a blueprint for those favoring more government action.

When I say “mitigation” in the following discussion, I mean actions taken well before specific consequences are realized toward broad goals like reducing global carbon emissions. When I say adaptation, I’m referring to a point we haven’t reached yet, including ex-post response to specific events like the ones listed in the table above and ex-ante preparation when the likelihood of specific events happening becomes clearer.

Mitigation of the impacts of climate change involves coordinating the actions of every person, firm, and organization on the planet. My contention is that any society preserving even basic individual rights will struggle to accomplish this goal both with the government and private sectors. But a complex, commercial society is made to adapt. Those who consider even discussing adaptation a sort of gnostic intentional defeatism are well advised to review the “1.5 degrees” column of the table above to see what we already likely face no matter what else we mitigate.

Nation-states face enormous problems when trying to marshall the combined efforts of their populations. There are huge informational problems and limits to what centralized planning can calculate or know in a qualitative sense. For an example see my colleague Phil Magness’ critique of the carbon tax–even determining the right level of such a tax is well beyond a central authority’s capability.

These efforts become even harder when the consequences we’re trying to avoid are at least a generation down the road and inherently uncertain both in severity and time, place, and nature of impact. When AOC made her much-criticized comparison to the Second World War, she was trying to evoke a kind of clear and present danger. Without one, a second class of political problems from interest groups to overall factionalism take root and prevent any action.

The private sector also faces huge challenges when trying to mitigate a series of events as complex as climate change. The free-rider problems at this level are dizzying–what manufacturer will take highly costly steps to reduce emissions on its own?

All of these problems mean we must look at the other side of the coin: adaptation.

The Real Deal

We tend to reduce the idea of “climate change” to a single disaster – according to the predictions from the UN reports, it’s more like a suit of slow changes in averages in our weather, from temperature and rainfall to sea level, coupled with a higher likelihood of natural disasters. It’s thousands of individual events varying greatly in nature, size, and scope.

This is where a society with a free and well-developed private sector ought to shine. The engine of entrepreneurship combined with people responding to facts on the ground with which they alone are intimately aware will yield countless inventions, new construction, and other initiatives great and small. “The private sector” as a whole probably won’t get its due from pundits when the world is adapting to climate change since by its very nature its responses will be decentralized and often hidden in plain sight.

We can speculate all we want on entrepreneurial solutions to problems that haven’t yet materialized–but the private sector can shine exactly where our speculation, and that of the public sector, inevitably falls short.

Forbes contributor Willy Foote writes, “We need a comprehensive global effort to both mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change. But the latter is not a secondary challenge that can be put on hold until the world solves the former. It’s an immediate need.” The private sector is where much of this action will happen: “Social entrepreneurs, investors, and other private actors—unlike most governments—have inherent flexibility. They can experiment, identify the best solutions, and share that knowledge with others.”

The environmental left is becoming less shy about wanting to greatly reduce the size and influence of the private sector. Climate change shows why we need a strong private sector–truly unleashing global knowledge and ingenuity to address changes around the world.