Is There Such a Thing as a Free-Market Gold Standard?

Twice recently I’ve come across arguments to the effect that, despite what some libertarians, goldbugs, cryptocurrency fans, and Fed Board candidates imagine, the idea that the historical gold standard kept governments from managing money, leaving the job to market forces, is a myth.

In his June 24th piece criticizing Facebook’s Libra Currency, which is being marketed as a sort of international stablecoin, Barry Eichengreen writes:

Mercifully, Facebook avoided the idea that a stablecoin will free us from the tyranny of the Federal Reserve. Typically, stablecoin purveyors invoke a mythical past in which the monetary unit of account was free of government manipulation and backed by tangible assets, such as gold in the 19th century. But as any historian will tell you, the 19th-century gold standard never operated this way. Governments were always involved. The gold backing of national monies was at most partial. Still, these simple facts don’t prevent the libertarian advocates of stablecoins from abusing the analogy.

More recently Greg Ip, in a WSJ article questioning Judy Shelton’s merits as a prospective Fed governor, made a similar point. “Goldbugs,” he says,

claim the gold standard takes away politicians’ and unelected central bankers’ control of interest rates, which they consider antithetical to free markets. … But it is a myth to claim the gold standard obviated discretion. Someone had to decide which metals would back the currency, and at what price, and how much gold had to be kept in reserve per unit of currency (the gold-cover ratio).

Even on gold, central bankers still had to decide interest rates. Whereas those decisions are now guided by inflation, unemployment and growth, back then they were also guided by the amount of gold in reserve. If gold was fleeing to other countries or stashed under people’s mattresses, the central bank had to raise interest rates to bring it back.

Although I’m neither a goldbug nor sold on Libra (the workings of which remain something of a mystery), and I’m happy to concede there has never been such a thing as a pristine free-market gold standard, I think that Eichengreen and Ip exaggerate the role government authorities played in “manipulating” or otherwise managing the historical gold standard. Moreover, I believe that the role of some governments was sufficiently small to justify treating their nations’ gold standards as “free market” systems, meaning ones in which market forces, including bankers’ pursuit of profits, rather than government-dictated policies, ruled the roost.

Many gold standard countries lacked central banks

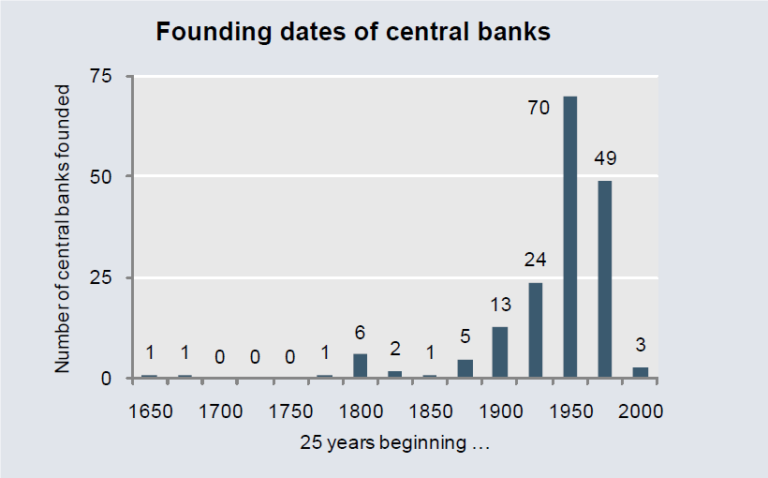

Let’s start with the easy part: Greg Ip’s claim that “Even on gold, central bankers still had to decide interest rates.” That claim would have merit if all the nations that took part in the classical gold standard (1871-1914) had central banks. In fact, most didn’t. As the following chart, reproduced from a BIS publication, shows, the vast majority of today’s central banks were established after the classical gold standard era. Gold standard nations that lacked central banks throughout the classical gold standard era included the United States (one of the “core” nations), all of the British Dominions save Australia (which only established a central bank in 1911), Greece, Turkey, the Philippines, Thailand (Siam), and all of Latin America. Because the Swiss National Bank wasn’t up and running until 1907, Switzerland also lacked a central bank for most of the classical gold standard era.

Some nations hardly regulated their gold standards at all

That some gold standard nations lacked central banks doesn’t necessarily mean that the governments of those nations didn’t manage or manipulate their gold standards, by setting interest rates or otherwise. In the United States, for example, Civil-War era currency and banking reforms resulted in a notoriously “inelastic” currency stock. Thanks to that, and to other legal restrictions, including barriers to branch banking and minimum bank reserve requirements, U.S. interest rates were notoriously unstable, with a tendency to rise, sometimes sharply, every harvest season. To combat that tendency, Dick Timberlake explains, during his tenure as Secretary of the Treasury (1902-1907) Leslie Shaw made a point of transferring sub-treasury gold to national banks as the demand for currency and bank credit reached its seasonal peak. Shaw’s actions showed that governments don’t have to rely on central banks to deliberately influence interest rates.

But the U.S. was only one of many classical gold standard participants that had no central bank. In others, government influence on interest rates and other monetary magnitudes was practically absent. Canada is a good example. There interest rates were relatively stable, not because the Canadian government interfered to make them so, but because Canadian officials avoided the sort of harmful interference that destabilized U.S. rates. In particular, they allowed Canadian banks to branch freely, and to issue notes backed by their general assets (and not solely by government securities, as in the U.S.). And although entry into the Canadian banking system was limited by would-be bankers’ need to secure government charters, bona fide applicants were never turned down so long as they met minimal capital requirements that were relatively modest until 1890.

That’s not to say that the Canadian government didn’t play any part in Canada’s gold standard regime. Most importantly, it issued so-called “Dominion notes,” while making them legal tender. It also prohibited Canada’s chartered banks from issuing notes under $4 (increased to $5 in 1880), so as to give itself a monopoly — strictly for revenue reasons, by the way — of smaller denominations. Nevertheless the Dominion note regulations were such as caused this intervention to differ little from one in which Canada’s chartered banks alone issued paper currency. As Ronald Shearer and Carolyn Clark explain,

Canada adopted the gold standard in 1853. By 1913 it had crystallized into what Keynes called a “fixed fiduciary issue” system… . Legal tender was either gold coin or Dominion notes, a government-issued currency. Beyond a basic fiat issue ($22.5 million), these notes were subject to a 100 percent gold reserve. Chartered bank notes circulated alongside Dominion notes, but were not legal tender, and bank deposits were of increasing importance. Banks were required to convert their notes and demand deposits into Dominion notes (or gold) on demand and for this purpose held substantial reserves of both Dominion notes and gold. However, there were no constraining cash-reserve requirements.

The Bank of Montreal acted as the government’s fiscal agent and on rare occasions performed some central-banking functions (for example, during the financial crisis of 1907). However, there was no central bank; indeed, the very concept was anathema to a large part of the banking industry.

In fact, 1907 was the only important occasion before War War I (and the end of the classical gold standard) when the Canadian government, using the Bank of Montreal as its agent, lent money to Canada’s banks. And in that instance, Georg Rich points out, the request for aid “originated entirely with Western agricultural interests.” “The chartered banks were reluctant to participate in the scheme” and “did not need help.” Setting aside this one “highly controversial departure,” Rich observes, “the pre-1914 Canadian gold standard [operated] with a minimum of government intervention on the money and foreign exchange markets.”

In light of Eichengreen and Ip’s remarks, the fact that Canada’s banks weren’t subject to reserve requirements is particularly worth noting. It means that, in Canada at least, it wasn’t the case that “someone” (presumably meaning some government official or officials) “had to decide … how much gold had to be kept in reserve per unit of currency (the gold-cover ratio).” Although there was, as we’ve seen, a fixed gold cover requirement for Dominion note issues, and Canadian banks had to keep at least half of their reserves in the form of Dominion notes, the banks were allowed to choose their own gold-plus-Dominion note reserve ratios and to let those ratios fluctuate according to their own risk-return calculus. That in practice they chose relatively modest ratios proves, furthermore, that the “partial” gold backing of a gold standard nation’s money wasn’t itself evidence of any government interference. On the contrary (and despite what some hard-money fans think), fractional reserves have always been the default free-market arrangement.

Central banks that did take part in the classical gold standard didn’t “manage” it all that much (or all that well)

Canada was, of course, not only a “peripheral” gold standard country but part of the British Dominion. It’s therefore tempting to suppose that it fell under the orbit of the Bank of England, allowing it to indirectly “manage” Canada’s monetary regime. This view fits in, after all, with the common belief that the Bank of England played a central role in managing the classical gold standard regime as a whole.

Even so, there’s no basis for it. During the classical gold standard era the Bank of England never acted as a Lender of Last Resort to Canada’s chartered banks.* When those banks needed gold they looked, not to England, but to the United States, and particularly to the New York money market. And their dealings in that market were, needless to say, entirely private matters: Canada got as much gold or foreign exchange as it could afford at the going rate, and not a penny more. What’s more, as Georg Rich has pointed out, “in periods of severe financial stress, Canada typically acted as a lender to the New York money market” (my emphasis), not as a borrower.

More fundamentally, if some authorities are to be believed, the Bank of England’s role in managing the gold standard on England’s behalf, let alone on behalf of other nations, has not been nearly so great as many suppose. Giulio Gallarotti, a Professor of Government at Wesleyan and the author of The Anatomy of an International Monetary Regime: The Classical Gold Standard 1880-1914, denies that the Bank played a crucial part:

Not only can we say that the Bank did not manage the international monetary system, but it is questionable whether it even managed the British monetary system. The Bank actually acknowledged little responsibility for the British monetary system itself. In fact the Bank’s own private goals often worked to the detriment of the British financial system (i.e., was [sic] a source of destabilizing impulses for British finance). In the role of British central banker…it consistently showed itself to be a poor guardian of the monetary system [and] its behavior in crises suggests that it may have more often compounded financial distress than mitigated it.

Gallarotti goes on to observe that “These outcomes are all the more visible at the international level. The Bank was even less an international than a domestic central banker.”

Nor is it so hard to imagine a completely free-market gold standard

Allowing that a gold standard doesn’t have to be managed by one or many central banks, does the very existence of such a standard not require some direct government action? Mustn’t the government choose the basic gold unit, and supply coins representing it? Mustn’t several governments cooperate to establish an international gold standard?

The short answer to all three questions is “no.” But defending it requires that we venture beyond the confines of post-1870 monetary history, and even beyond those of monetary history of any sort, and into the realms of anthropology on one hand and imaginative (but nonetheless reasoned) speculation on the other.

That the decision to treat gold as a money commodity needn’t be one reached by bureaucrats has been famously argued by Carl Menger, in his essay “Geld,” originally published in 1892 (with an English translation in the Economic Journal ), and expanded in 1909. To be sure, Menger’s theory doesn’t describe the only way in which gold (or some other commodity) might come to be employed as money: other factors, including the dictates of political authorities, can also play a part. Still it shows that political dictates aren’t necessary.

But gold isn’t like cowrie shells or tobacco leaves. It doesn’t come in “natural,” relatively uniform units. So doesn’t it take government to define one? And doesn’t that mean that no gold unit of account can be entirely “free of government manipulation”?

No again. The same year in which Menger’s essay appeared in the EJ, anthropologist William Ridgeway published The Origin of Metallic Currency and Weight Standards, a now-classic study in which (as I’ve written elsewhere) he categorically rejects

the view that ancient weight units “had been obtained scientifically,” which he attributes to a false analogy with the metric system established by the French Republic. “Reflection,” Ridgeway says, “might have shown scholars that even the French system was not a wholly independent outcome of science, for beyond doubt the métre and litre and hectare were only varieties of older measures of length, capacity and surface, then for the first time scientifically adjusted.” Instead, he argues, ancient gold monetary units were a natural outgrowth of traders’ premonetary habit of expressing prices in terms of oxen or cows. … As oxen were worth about 130 grains of gold throughout the ancient world when gold came to be employed as an exchange medium, that quantity of gold became the basis of the earliest gold units, and eventually of coins representing those units. This simple transition, Ridgeway observes, accounts both for the surprising uniformity of independently developed gold units throughout the ancient world, and for the tendency for the name of the old barter unit to attach itself to the new metallic ones. In ancient Athens, for example, the first current gold coins bore the symbol of an ox, and values continued to be expressed in ox-units, though those units were now represented not by oxen themselves but by their metallic value equivalents. The same development is reflected in the various monetary terms having the latin word pecunia as their root.

The conversion of raw gold into reliable coins conforming to a standard weight unit also didn’t have to be a government undertaking. It’s not clear — and it probably never will be — whether the very earliest coins were struck by tyrants or ordinary (if very well-to-do) citizens. (For an extended, recent exchange on the topic see here, here, here, here, and here.) And it’s true that throughout history governments have tended to monopolize coinage, allowing coins to be both privately-minted and privately-issued only on rare occasions. Those exceptions, involving gold as well as token coins, suffice nonetheless to show that the private sector is perfectly capable of manufacturing and supplying coins that reliably represent established metallic units.

Of these rare episodes, the private minting of gold coins during the California gold rush, and for several years afterwards, is most relevant here. The story has been well if briefly told by Brian Summers. (Those wanting further details may consult numismatist Edgar Adam’s classic work.) The bottom line is that, although some of California’s private mints struck mediocre coins, others struck coins of exceptionally high quality, and those are the mints that prospered. In short, the business worked like many other competitive industries, such as those that produce paper clips, light bulbs, and No. 2 lead pencils.

Incidentally, until 1908 — that is, for most of the classical gold standard period — the Canadian government produced no gold coins at all. Instead, American gold eagles and British sovereigns supplied the gold-coin needs of Canada’s Treasury, chartered banks, and citizens. It calls for no great leap of the imagination to envision those same needs being met using coins custom-made for the purpose by a handful of reputable private firms.

Finally, although the multiplication of national gold standards that gave rise to the classical gold standard was partly accidental and partly the outcome of deliberate legislation, market forces also played an important part in it — so important, indeed, that Gallarotti goes so far as to declare the classical gold standard “spontaneous monetary order.” “No one,” he says, “intentionally set out to create an international gold standard. Whatever efforts took place at monetary conferences to build a gold monetary union failed.” Instead,

The ideology of gold created focal points which made gold attractive as a monetary standard in the latter-19th century. Consolidation of the gold bloc occurred swiftly as supply and demand conditions for precious metals imparted a robust self-propagating quality onto gold.

According to Chris Meissner, network externalities also played an important part in the classical gold standard’s development. “Joining the gold standard,” he says, “decreased the costs of trade with other gold standard countries. Consequently, countries adopted gold sooner the more they traded with other gold standard countries.” Although the process got started thanks to “a small number of historical events” (Newton’s rating of the guinea and the discovery of gold at Sutter’s mill come immediately to mind), “once the process was set in motion, a more deterministic path based on economic fundamentals was followed.” The process Meissner describes is in fact but a continuation, played out on the global stage, of the one Carl Menger first theorized about.

It’s nevertheless impossible for a government or governments to reestablish a “free-market” gold standard

I’ve argued that a free-market gold standard is certainly conceivable, and that the classical gold standard was in fact one in which market arrangements and forces played a far greater role than is often supposed. It doesn’t follow, though, that I agree with those goldbugs who suppose that the United States could once more have a market-based monetary system if only the government would fix the dollar price of gold, by once again making paper dollars redeemable in gold or otherwise.

Why not? First of all, because it isn’t 1934 anymore. Federal Reserve dollars have long ceased to be promises to pay gold, or anything else. That reality is reflected in all prices and contracts. There is no longer any sense in which restoring the gold dollar, convertible or otherwise, could be construed as a mere honoring of previous contractual commitments. Bygones are bygones.

Instead, any official effort to link the dollar to gold today would be just another act of monetary central planning. The plan might, to be sure, attempt to replicate a past relatively market-based monetary arrangement. But it would be a central plan nonetheless, having no greater claim to legitimacy than any other plan the government might put into effect using established legislative procedures. Were the U.S. government to establish a gold standard today, a future Barry Eichengreen or Greg Ip would be perfectly right to say, looking back, that the new standard, far from being a product of the free market, was a result of government intervention, if not something the U.S. government imposed on at least some of its citizens.

In other words, an official reform linking the dollar to gold today wouldn’t be any more “free market” than one that linked it to silver, durum wheat, or bitcoin. Nor would it be any more free market than a plan to target NGDP futures. Yes, these are all schemes for limiting monetary authorities’ discretionary powers, and for thereby placing monetary policy more firmly in the grip of rule of law. As such any might lay claim to being capable of helping to enhance the security of property that’s essential to the workings of free markets. But none can claim, a priori, to be uniquely consistent with the flourishing of such markets, let alone a spontaneous outcome of their operation. Instead these and other potential reforms must be judged by their merits. We can and should let history inform that assessment. But we shouldn’t let ourselves be slaves to it.

None of this means that a future free-market gold standard is altogether impossible. It’s possible that such a standard could re-emerge spontaneously, if only governments would let it, and provided they did away with all existing barriers to currency competition, creating a level playing field for all established and potential currencies to play on. I reckon myself a fan of currency competition, and I wish good luck to all entrepreneurs seeking to supply alternatives to established national monies, provided they do so by honest and non-coercive means.

But we mustn’t overestimate the likelihood that any such alternatives can displace a national currency as well-established as the present U.S. dollar, or even any that is not depreciating extremely rapidly. The same network effects that made the spontaneous evolution of a gold standard possible in the past also make it very difficult for an upstart would-be monetary standard to gain converts once an established monetary standard, whether gold or fiat, is in place.

_________________

*The Bank of England did of course occasionally act as a domestic lender of last resort. But according to at least one authority its doing so reflected, not the inherent need for such a lender in any gold standard arrangement, but — on the contrary — the need for it to compensate for the otherwise destabilizing influence of its monopoly privileges (and corresponding limited powers of other English banks). The authority in question was none other than Walter Bagehot. (Note added 7/9/2019.)

The original of this piece ran on Cato’s Alt-M blog.