The FTC’s Strategy Against Facebook is Bad Economics

Big Tech companies, including giants like Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple, have become emblematic of the renewed push in some circles for a more aggressive and activist antitrust policy. The facts surrounding these firms and markets do not rise to the consumer-harm standard embraced by antitrust enforcers since the 1970s. Still, in the wake of scrutiny over data and privacy concerns some observers see Big Tech as a proving ground for central planning via antitrust enforcement.

Last month the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission joined the party when we learned they were pursuing major investigations of the four most prominent tech giants. Now, some more details of the FTC’s thinking behind its investigation of Facebook have become public.

The Wall Street Journal reports that the FTC is scrutinizing Facebook’s acquisitions, including photo-sharing app Instagram in 2012 and messaging app WhatsApp in 2014. The question is whether Facebook bought these firms as a preemptive strike against fair competition, preventing them from growing and maturing into true competitive threats.

While the rise of Big Tech poses real challenges worthy of thought and debate, the FTC’s strategy reveals fatal flaws in the idea of using antitrust law simply to make companies do what we want them to do. The theory that Facebook acquired Instagram and WhatsApp primarily to squelch future competition represents a view of antitrust that is simplistic and naive. It also endangers a startup business model that has produced incalculable benefits through innovation.

Neglecting Economics

Suppose you are the owner of the only supermarket in a small town. A smaller mom-and-pop store opens down the road, perhaps offering better prices or products. You see the potential for the store to expand and take away your customers. You make the upstarts an offer they can’t refuse, buy their store, close it, and rent the property out as office space. Monopolist’s crisis averted.

The problem with the FTC applying this theory to Facebook is that the social media market is nothing like the highly stylized textbook model of competition I tried to replicate above. In focusing on this theory, the FTC neglects a stunning number of economic concepts, including, but not limited to, network effects, product differentiation, platform competition, disruptive innovation, economies of scale, economies of scope, and market definition.

As it became synonymous with social media, Facebook evolved into an all-encompassing platform that included photo sharing and messaging. It isn’t clear whether the FTC’s vision of a world but for Facebook buying Instagram and WhatsApp involves competition between many smaller all-encompassing platforms, or competition by a different set of firms for each function Facebook performs.

In the wake of Facebook’s early dominance in the social media space, it clearly made the most sense for startups Instagram and WhatsApp to specialize in one specific function and differentiate themselves on the quality of their service. Whether they would or could parlay that success into becoming Facebook’s competitors across a suite of services is speculative at best. And were that the case, the gain to consumers from that competitive discipline would have to go a long way to outweigh the cost of having friends on different networks and redundantly using several platforms.

If we instead focus on competition for individual features, the FTC would have to establish that innovation and quality are lower in a world where Facebook owns and integrates Instagram and WhatsApp than a world where it competes with them using its original in-house versions of these features. This claim is dubious for at least two reasons.

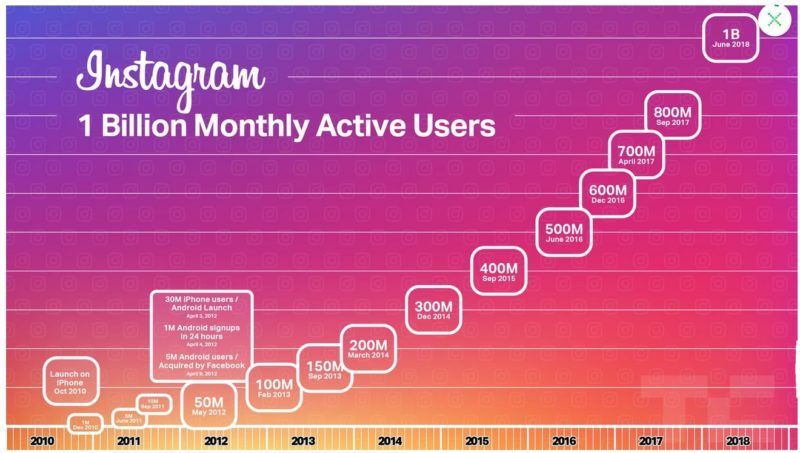

First, unlike the supermarket example above, Facebook did not shut down Instagram and WhatsApp: their standalone versions are still available and widely used, and Facebook has also integrated their capabilities into its wider ecosystem. The number of Instagram users, according to the chart below (reprinted from TechCrunch), increased twenty-fold from the time of Facebook’s acquisition to last year. Viewing such an acquisition as an anti-consumer move would take a level of imagination rarely attributed to the government.

Second, Facebook does not only compete with other social media platforms and applications. As anyone who has lamented people spending too much time on social media knows, it also competes with other entertainment activities, other social activities, time in school and at work, and time with family, to name a few. Facebook therefore has an incentive to make its applications as innovative and high quality as possible even without several upstarts nipping at its heels.

Vox, which now sings the virtues of aggressive antitrust action against Big Tech, understood the virtues of innovation and growth within Facebook back in 2017. Quoting author and former Facebook executive Mike Hoeffinger, they wrote:

And therein lies the priceless value of the Instagram story: proof of existence that Zuckerberg can turn visions of growth and impact into reality without undue meddling.

Barriers to Prosperity

The internet boom two decades ago demonstrated the special importance of startups in high-tech industries. Because the vast majority of startups fail, motivating their creation in the first place requires an especially large pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

The only statistic you need to know is that among successful startups, 16 times more are bought by larger firms than issue their own IPO. Getting bought is the realistic light at the end of the tunnel for the quintessential computer geek toiling away in their garage. Major antitrust decisions with a chilling effect on big firms buying smaller ones in the tech space calls that path into question.

The FTC’s current course would effectively erect new barriers to entry in countless markets for technology. Such barriers are harmful in any industry; in high tech, they risk destroying the evolutionary process of startups that is a crucial source of growth in 21st-century advanced economies.

A Dangerous Distraction

Advocates of an aggressive new approach to antitrust are concerned about the influence of tech giants, and large corporations in general, on society. Their chosen strategy may be the quickest way to bloody these corporations’ noses, but it will do much harm and very little good.

We live in a world still evolving and reacting to the technological revolution of the past few decades. The data scandals of the last year have brought into clear relief that this new world presents challenges everyone must take seriously. But attempting to twist antitrust enforcement into corporate social engineering is both shortsighted and likely disastrous.