The Money Museums of Canada

Being a visiting scholar at the American Institute for Economic Research is an honor. It gives students the chance to dive deep into their research and accomplish great things. Students such as us are fortunate enough to enjoy the magnificent AIER campus with its library and dedicated staff, not to mention its beautiful surrounding nature. We are also granted frequent contact with the best academics in their fields.

Right now, AIER hosts three visiting scholars from Europe: Joakim Book from Sweden, Lex van den Eersten from the Netherlands, and Sven Schütt from Germany. We are all very much interested in markets and monetary economics as well as the history of the institute.

AIER was founded on the principle of sound money and has always had a strong connection to gold. To balance all the research and theoretical work we are doing on campus, we went on a field trip to Ottawa, the city hosting the Canadian central bank museum as well as the Royal Mint of Canada. Digging deeper into the fascinating subject of economic and monetary history, we discovered quite a few remarkable things about America’s northern neighbor.

Canadian Free Banking

The Canadian episode of free banking (a lightly regulated banking sector without a central bank), ranging roughly from 1817 to the establishment of the Bank of Canada in 1935, is a much-celebrated and much-researched episode in the literature on free banking. In contrast to America, with its many banking crises during the 19th century, Canada saw no systemic banking crises and was robust to the kinds of financial shocks that crippled many American banks.

In one pertinent display of how government-controlled central banks with the potential for unlimited money creation are far from essential for a stable banking system, the Bank of Montreal, which we also visited, in October 1907 simply took over the Bank of Ontario’s liquidity troubles. Without a bank run, government deposit insurance, or a last-minute negotiated emergency package, Bank of Ontario customers were simply greeted by a notice the next morning saying “This is the Bank of Montreal.”

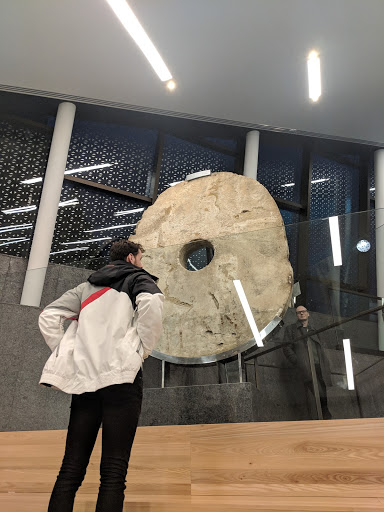

Stone Money: Rai from the Yap Islands

Many people might be familiar with the various kinds of objects that were historically used as money in colonial North America (furs, salt, tobacco, wampum, codfish) or elsewhere around the world (maize, corn, cattle, feathers). One of the most bizarre stories comes from the Yap Islands in the southwest Pacific, as made famous in Milton Friedman’s 1991 article “The Island of Stone Money.” An original, the large round stone object used as money, weighing thousands of pounds, stands in the entrance of the Bank of Canada Museum for anyone in search of a salient reminder that many things of various degrees of portability and tangibility can play the role of money in society.

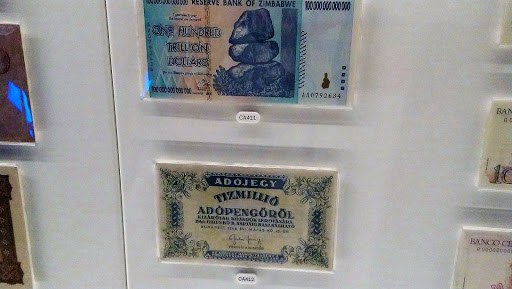

Among the notes in the Bank of Canada’s collection are some of the highest-denomination notes the world has ever seen. Whenever governments and central banks have excessively printed money unchecked by underlying commodities such as gold, huge price inflation has followed. The most eye-widening such instances are captured in economics professor Steve Hanke’s hyperinflation tables and are nothing short of incredible. Countries competing for the undesirable place of worst hyperinflation in history boasted annual inflation rates of millions and billions of percentage points. To better illustrate the numbers, Hanke reports the time required for prices to roughly double. Yugoslavia in the early 1990s needed about one and a half days for prices to double, for a mere third place on the list. More recently, Zimbabwe in 2007–8 needed just over 24 hours for prices to double. An infamous Z$100 trillion Zimbabwean note can be found in the Bank of Canada’s collection. As for the unthreatened leader of hyperinflations, Hungary in 1945–46 (where prices doubled roughly every 15 hours), the Bank of Canada has a 10 million pengő note, which is in fact not the biggest denomination that the Hungarian National Bank issued: 1 sextillion pengő (1021). In the collection are hundreds of banknotes from all around the world of both earlier and much more recent time periods. At the Royal Canadian Mint, we learned how bullion coins are made and the history of the process. A bullion coin is per definition a coin used not for circulation but rather as an investment coin. It is commonly struck from silver or gold in identical standardized versions and is kept as a store of value. The process to guarantee the purity and perfection in creating the coins is impressively detailed by the museum. Compared to the most famous investor coin — the Krugerrand from South Africa — the Royal Canadian Mint’s flagship coin, the Maple Leaf, has an even higher fineness (.99999). Unfortunately, the tour does not come with a free Maple Leaf coin (with a market value of above US$1,200), but we got lucky to get a photo with 480,000 reasons to love gold. We would like to thank Edward Stringham, the president of AIER, as well as AIER itself for giving us this great opportunity to stay here doing our research and having these great experiences.

Gold Coins at the Canadian Mint