To Save Cash from Extinction, Consider Banknote Lotteries

A few years back, Brett Scott wrote a classic anthem to “grungy and unsexy” cash:

As unsexy an analogue as cash is, it is resilient. It is easy to use. It requires little fancy infrastructure. It is not subject to arbitrary algorithmic glitches from incompetent programmers. And, yes, it leaves no data trail that will be used to project the aspirations and neuroses of faceless technocrats and business analysts into my daily existence.

I agree. Cash provides the resilience, privacy, and censorship resistance that digital types of payments do not. What’s more, cash is vital to some of the more vulnerable members of society, including the poor, new immigrants, the young, and the elderly.

Cash’s usage in payments has been steadily declining as a percentage of all payments, especially in the developed world. Given the list of cash’s advantages, it’s probably worth the effort of protecting this grungy and unsexy payments option. But what can we do?

Last year I wrote about the Swedish central bank’s campaign to modify the concept of legal tender so that retailers are forced to accept banknotes. And many cities in the U.S. are now passing legislation that bans cashless stores. Other approaches include obligating all bank branches to provide cash withdrawal and deposit facilities.

But these fixes are heavy-handed. And they are only Band-Aids. None of them solves the underlying problem: cash is becoming less convenient relative to many of its digital competitors. My preferred approach to resuscitating cash is to try to make cash better. Why not introduce a banknote lottery?

One of the drawbacks of cash is that retailers and other participants in the cash-usage chain incur significant storage and handling costs. Compounding this problem is the fact that cash doesn’t pay interest. The hassle and inertness make cash an expensive payment option for stores to support. No wonder so many of them are choosing to go cashless.

As card payment-processing times decline and online shopping grows, cash becomes less attractive for consumers. Checking-account balances earn small amounts of interest, and savings accounts even more. Credit card transactions provide points and rewards. But banknotes don’t offer a pecuniary return.

If banknotes were to yield interest, they would become more competitive. An interest rate carrot might entice retailers to continue supporting cash payments and consumers to keep more of the stuff in their wallets. This might halt, or at least slow, some of cash’s declining share in payments.

The easiest way to pay interest would be to introduce a banknote serial-number lottery. Each week the central bank would announce a list of winning banknote serial numbers. Whoever happened to hold the winning notes could mail them in to the central bank in return for a much bigger check. Or they could turn it in at a local convenience store, drugstore, or bank, which would pay the owner a cash reward. These middlemen would, in turn, forward the note to the central bank for reimbursement.

A banknote lottery would be relatively easy to set up. Banknotes don’t have to be modified. The serial numbers are already there. And banknotes are already replete with anti-counterfeiting features. So the problem of fake lottery tickets would be nil.

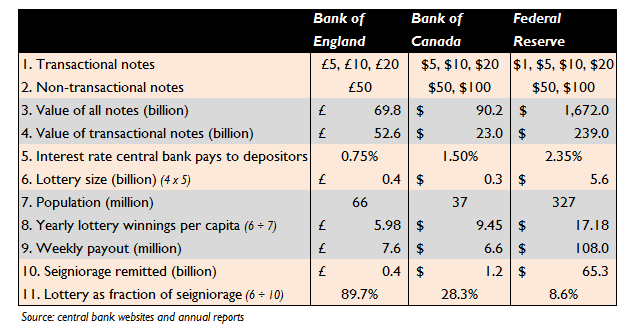

How much of a reward should a note lottery pay? Let’s take the U.S. as an example and imagine what a Federal Reserve note lottery would look like. Only those notes routinely used in transactions would qualify for the lottery: the $1, $2, $5, $10, and $20 notes. The total value of this transactional stock of notes comes to $239 billion, just 14 percent of all U.S. banknotes outstanding.

A Federal Reserve banknote lottery should pay no more than 2.35 percent per year. That’s the rate that the Fed currently offers to depositors. So, over the course of 2019, the Fed would pay around $5.62 billion in winnings ($239 billion x 2.35 percent). That comes out to $17.18 per American. Put differently, the Fed would offer $108 million in prize money each week.

There are a number of ways to distribute the $108 million. Once a week the Fed could announce, say, three lucky serial numbers that win a jackpot of $10 million each. A block of 500,000 or so winning numbers would split the remaining $78 million, getting $150 each. The Fed wouldn’t list all 500,000 winners. Such a list would be too grueling for players to parse. Rather, any serial number starting with an A and ending with a five might be a winner, or some such convenient combination.

The Fed would have no problem funding a yearly $5.62 billion lottery. In 2018 it forwarded $65.3 billion in earnings, or seigniorage, to the government. With a note lottery, $5.6 billion of this would be redirected to cash-using citizens and businesses, leaving a healthy $59.7 billion for the government.

In the table below I’ve provided statistics for a hypothetical lottery in the UK, Canada, and the U.S. Note that the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada would have to sacrifice a much-larger percentage of their seigniorage in order to run note lotteries. That’s because foreign usage of US$100 notes provides te Fed with a larger flow of seigniorage.

How would a note lottery affect cash usage? Over the last decade cash as a transactions medium has been buffeted by a vicious circle. Reduced cash usage by consumers has led to fewer stores accepting it, which in turn has led to less consumer usage. A lottery could reverse this.

All commercial participants in the cash chain — retailers, cash-in-transit firms, banks, and ATM companies — would be able to monitor their inventory of small-denomination banknotes for winners. This new flow of income would defray their handling and “shoe leather” costs. Presumably stores and banks would be less likely to go cashless. Consumers who have long since deserted “grungy and unsexy cash” might be drawn back by the thrill.

Renewed usage of cash would preserve the small island of financial privacy that citizens currently enjoy. It would also ensure that a robust backup payments system continues to exist. Cash-dependent members of society wouldn’t have to worry about getting locked out by digitization of payments. To top it off, low-income cash users would also finally receive a return on their savings.

That ticks a lot of boxes, no? For those who are interested in preserving cash, perhaps it’s time to start talking about banknote lotteries.