Why Do Central Bankers Change Their Tune?

Much has been made of modern central bank independence. While the history of central banking is filled with shady bargains between sovereigns and powerful financiers, exchanging monopoly charters for premium borrowing terms, today’s central banks are disinterested experts devoted to the common good through stewardship of the macroeconomy.

US central banking history is different. We never had an ‘imperial’ central bank. Instead, the Fed’s historical sin was putting the Great in Great Depression. But now, armed with knowledge from modern monetary economics and insulated by pressure from the Treasury, the Fed is free, along with other central banks in liberal democracies, to fulfil their mission as benevolent technocrats.

There’s just one problem: as my colleague William Luther has recently argued, it’s all hogwash.

Take the case of the US. Although the Fed is formally independent of the Treasury, there are many, many informal ways that elected officials and their agents can pressure central bankers to behave in politically popular, but long-term costly, ways. Central bankers, especially those at the top, are political appointees. It is wishful thinking to imagine that they are thus immune from the vagaries of day-to-day politics merely because there are no explicit commands from the executive of legislative branches.

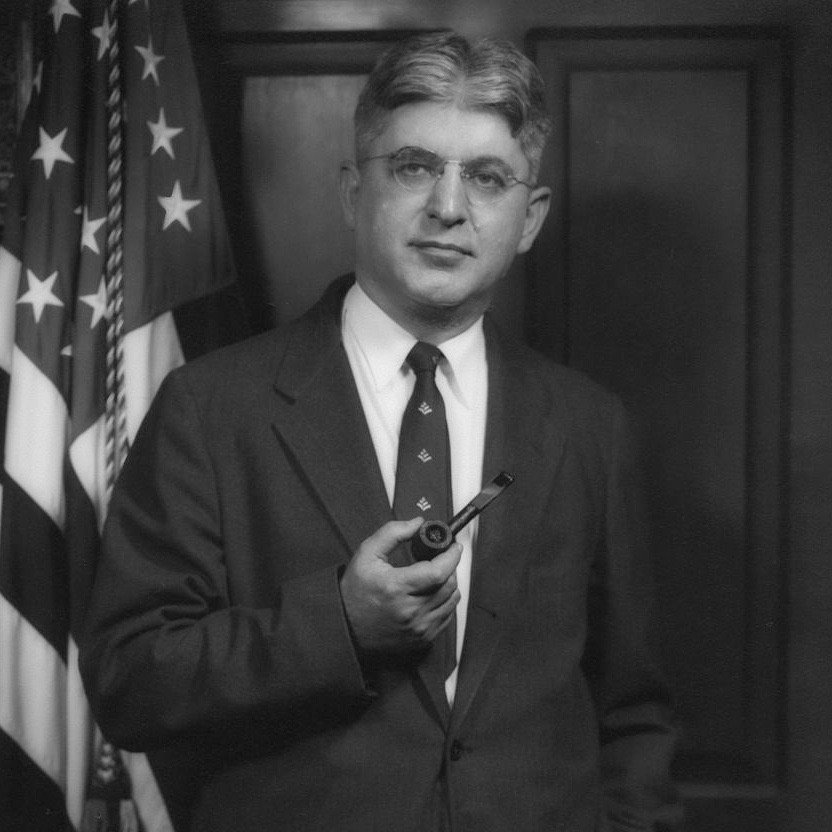

One interesting way we can see the effects of politics—or more properly, political institutions and environments—on monetary matters is to explore the tenure of recent Fed chairs. Specifically, we might compare public statements made during their tenure to the research and other writings published before they became political appointees. In a new working paper, Daniel J. Smith of Troy University and I do just that. We investigate the pre- and post-Fed appointment statements of Arthur Burns, Alan Greenspan, and Ben Bernanke to see how their views changed when they moved from nonpolitical to political positions. All three exhibited significant changes in their views on monetary economics, macroeconomics, and financial economics when they were put in charge of the Fed.

The nitty-gritty specifics are fascinating. But what’s relevant is the big picture. All three former central bankers wrote extensively about monetary policy both before and while serving as Fed chairmen. Before working at the Fed, they were relatively humble about the prospects of monetary policy to improve the economy. They emphasized the dangers in excessive monetary activism. During their time as Fed chair, the content of their writings changed significantly. They were much more likely to argue for active monetary management, retreating from their previous stances of humility and restraint. Furthermore, they became quick to disavow Fed involvement with any problems currently besetting the macroeconomy. In brief, their message became, “Whatever it is, the Fed must fix it; but if it goes badly, it isn’t our fault!”

How should we account for this? The simple answer is that it is the natural consequence of operating in a political environment, where informal pressure from elected officials and their agents cause even the most stubborn advocate of monetary restraint to shift their views at the margin to become more conducive to political goals. It is the politician’s syllogism at work: “Something must be done; this is something; therefore we must do this.”

Let me be clear: this is an argument about political environments and institutions, not personal character. We make no judgment either way about virtue or vice. Instead, we merely note that political environments, as filters, select for certain outcomes at the expense of others. Central bankers are not immune from this filtering process.

If we want sound money, we cannot afford to ignore the political process. Statistical and mathematical pyrotechnics are all well and good. But they can only complement, not substitute for, good old-fashioned political economy.