What to Read on Money

Money makes the world go ’round — and the study of all things money enthralls quite a number of economists. And for good reason, too. In modern market societies, money is on one side of every transaction: when you buy a car or pay for your groceries and everyday expenses; when you buy assets for retirement, tirelessly carved out from an income paid to you in money; when you clear out the garage and sell all the junk you’ve been storing up over the years.

What money is and what happens to money under modern monetary regimes therefore impacts everyone in society in a way that other objects of economic study might not. Indeed, the monetary system and the impacts on the real economy from its misconduct were a large motivation for our founder, E.C. Harwood, to set up the American Institute for Economic Research in the first place.

Every year, at the end of July and beginning of August, we pay some homage to that legacy by running the Harwood Graduate Colloquium on Monetary Policy back-to-back with AIER’s annual Sound Money Project meeting. For a full week, our beautiful campus is filled with graduate students eager to delve into the world of money, as well as established scholars presenting their latest research on topics as diverse as the Fed’s reporting bias, macroeconomic research, bitcoin as money, and issues of finance on the blockchain.

As an introduction to the topics that will be dealt with in our Graduate Colloquium, over the next few weeks I’ll be summarizing the core readings that our students are currently reading to prepare for a good discussion at the event. The four topics — money; monetary regimes and commodity standards; monetary policy; banking regulation — are all explored through three or four select readings, where some readings supplement a lecture by an established scholar and some form the basis for the Socratic discussion among the students.

Here’s a rundown of what’s in store for the Money segment:

Carl Menger’s “On the Origin of Money,” published in 1892, is the archetypical economic explanation for how money came to be. Versions of the story are included in every economics textbook: Menger describes in typical marginalist fashion how a society can center on a single object serving the functions of money, starting off from a position of barter — where holders of apples in want of oranges trade directly with holders of oranges who similarly desire apples.

The key word in Menger’s article is “saleableness” (saleability), roughly capturing how liquid an individual good is: if I have a hard time acquiring all the things I desire in exchange for my apples, I might be able to trade those apples for something that’s slightly easier to sell — say, for instance, a good that almost everyone in society uses, such as bread. Using the newly acquired bread, I expand the number of traders willing to trade with me and, though I have no intention of using the bread myself, I can in turn trade it for what I desire.

This transition from direct exchange to indirect exchange can gradually take place as a society’s members learn which goods are more easily used in trade — ultimately explaining how a society can center on using “little metal disks apparently useless as such” as money.

The second article is a transactions-cost spin on Menger’s article, written by Armen Alchian in 1977. Alchian conceptualizes money as a middleman between economic actors, an institution whose productivity is found in creating knowledge more cheaply than others. By doing so he pushes Menger’s insight further: it’s not enough to simply use a third good to offset the “double coincidence of wants” — any good would do that. To Alchian, the “costs of identifying qualities of a good are what counts,” and whatever emerges as money has the lowest costs of exchange — that is, it is easiest and cheapest for most actors in society to ascertain its quality and identify that as high-quality money.

By using a clear eight-by-eight grid system with experts and novices whose transaction costs differ from one another, Alchian’s detailed exploration illustrates how money is an efficient institution in reducing transactions costs among a society’s traders.

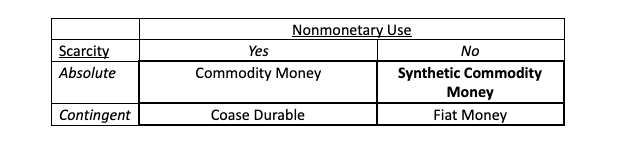

The next two articles, George Selgin’s “Synthetic Commodity Money” and Will Luther’s “Is Bitcoin Intrinsically Worthless?” are much more recent (published in 2015 and 2017) and use the rise of bitcoin to get at the core of what it means to be money. Selgin expands the dichotomy between “fiat money” (backed by government decree, “intrinsically useless,” which in monetary-economics speak means “no other economic uses”) and “commodity money” (some item useful in trade that’s taken on monetary roles over and above its use as a commodity). He adopts two different dimensions: monetary use vs nonmonetary use, and absolute scarcity vs. contingent scarcity, where the regular categories of fiat money and commodity money take up the long diagonal — fiat money is contingently scarce (we can create as much as we want) and has no nonmonetary use, whereas commodity money has nonmonetary use but is absolutely scarce (i.e., we can only get more by expanding valuable resources on prospecting and mining it).

Cryptocurrencies fall into the synthetic-commodity-money quadrant, having no nonmonetary use but being absolutely scarce through the strict money-creation arrangements of their individual protocols. Advantages of such systems include removing discretion in money-supply creation as well as letting accidental forces of nature impact the money supply; rather, the money supply is subject to “artificially arranged resource constraints.” A downside, however, is the inflexible response to money demand since — unlike gold, whose production and exploration is governed by the profit-and-loss mechanism and the price level — there is nothing in synthetic-commodity monies that can accommodate changes in money demand.

Luther’s article builds on these distinctions and delves deeper into the nature of bitcoin and how its rise squares with what’s known as the regression theorem — the idea that all monies in existence piggy-backed onto previous monies’ purchasing power when they came into existence. By formalizing a demand-for-money function consisting of monetary use and nonmonetary use, Luther also captures the network effect as it pertains to money.

Moreover, he illustrates a weakness of the regression theorem: bitcoin is either intrinsically worthless (no nonmonetary uses) or it has some nonmonetary use — such as, for instance, use as an internet token with mystical or curiosity value and other psychological and sociological values in signaling one’s group identity.

If it is intrinsically worthless, its rise is counter to the regression theorem: “The standard Mengerian process cannot account for the successful launch of an intrinsically worthless item.” If it is enough to have some obscure psychological value to pass the nonmonetary-use criterion, the regression theorem is a much-weaker explanation of how money today has derived its value and purchasing power. “Efforts to preserve the validity of the regression theorem,” Luther summarizes, “do so by eroding its practical relevance.”