How Top-Down Government Fails America’s Poor

A well-functioning society should provide a safety net for its members struggling the most. The unavoidable role of luck in market outcomes, the variability of circumstances in which people are born, and the imperative simply to alleviate suffering all speak to this need.

Our debate about safety nets and responses to poverty hinges on a fundamental fallacy — that services are either provided by the government or not at all. This falsely constructed debate diverts resources that could be used to directly help the poor, and often erroneously casts those favoring less government involvement in the economy as not caring about poverty.

This is the first in a series of articles that seeks to move our debate beyond false choices to potentially innovative ways to help people both get by and become self-sufficient. Though large-scale private philanthropy already exists alongside government programs, this series will focus on small, innovative community-based efforts, demonstrating the promise of voluntary decentralized institutions to address poverty more effectively than the top-down government programs on which the poor currently rely.

Before assessing both alternative governmental and private responses to poverty, this first article takes stock of the current landscape. In 2016 the U.S. government spent $877 billion on almost 100 anti-poverty programs. Rather than efficiently reaching its targeted recipients, the current kaleidoscope of programs provides a master class in how government dilutes help to its citizens through unnecessary planning, complexity, and bureaucracy. After being worked over for decades by the worst instincts of both the Left and Right, the social safety net the U.S. government provides to Americans earning the least is an almost-farcical maze of bureaucracy and complexity.

Bad Spending Habits

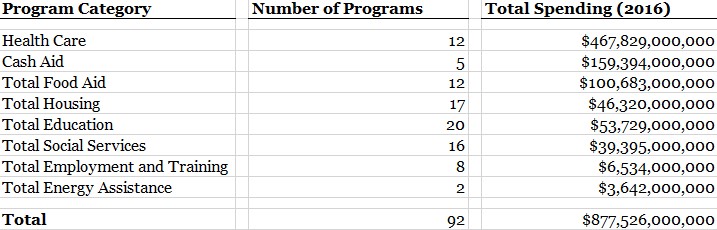

The table below summarizes the 92 U.S. government programs targeting low-income individuals, along with federal spending by broad category. While large corporations often hire million-dollar consulting firms to help navigate governmental complexity, those living below the poverty line obviously do not have that luxury.

Federal spending on programs targeting people with low income (2016)

The 92 programs tracked by the Congressional Research Service are virtually all targeted programs, aimed at money being used a certain way rather than giving program enrollees discretionary spending. For example, food aid programs include the National School Lunch Program, the Nutrition Program for the Elderly, the Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program, and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, to name only a few.

There were 40.6 million Americans living in poverty in 2016. The $877 billion that financed this social-service quagmire could have instead given every adult and child in poverty a check for over $21,000. Considering that this amount is well above the individual poverty line ($12,900), the current system must be subject to gross inefficiency. Granted, some of the programs included in the list are heavily targeted or involve specific subsidies such as higher education, but the spending relative to each person requiring aid remains astonishing.

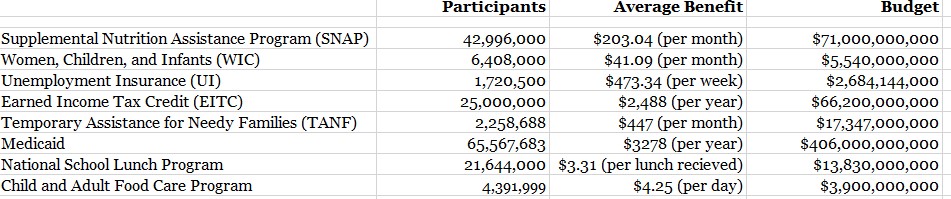

The table below provides number of participants and average benefits for several of the most popular aid programs.

Enrollees and average monthly benefits for selected government aid programs (2016)

Under the current system it is certainly possible to receive aid that brings one above the poverty line, but doing so is contingent on navigating multiple bureaucracies and selecting the right handful of programs out of nearly 100.

Big Brother Is Failing You

Our instinct, when confronted with a clearly broken system that wastes billions of dollars, is to dole out blame. There are government incompetence, backroom self-dealing, and some welfare recipients potentially free-riding off the system. But the blame game obscures what’s really going on. When we try to implement top-down programs at a national level intended to force or encourage people to make the “right” choices, we instead inevitably wind up with a muddled mess of rules and obstacles that seemingly defy common sense.

Politicians and intellectuals on the left and right both have plenty to say about how low-income Americans should live their lives. The Left frets that poor people will make unhealthy choices or not properly care for their children, while the Right sees moochers waiting for government handouts to avoid work.

Government can attempt to impose these choices either through non-cash aid or aid contingent on certain behavior. But the only way even a local government office can monitor the behavior in question is through bureaucratic processes. Virtually every major program listed in the chart above requires extensive paperwork, interviews, in some cases visits to medical professionals, and renewal often as soon as every few months.

People ordinarily make the choices that the Left and Right deem “correct” by responding naturally to their own wants and needs through countless day-to-day decisions reacting to self-knowledge so detailed that not even the most onerous bureaucratic process can come close to capturing. The inevitable results are the type of aid programs AIER Senior Fellow Michael Munger calls “aggressive, life-arranging, paternalistic, Big Brotheresque, police-state efforts at control rather than aid.”

Better Paths

As a society, we can do better at helping those most struggling by closing the book on centralized programs that make a social safety net contingent on “correct” behaviors. Two options, which we will consider in subsequent articles, are simplified government programs giving cash aid (such as universal basic income or means-tested basic income guarantees), and a more radical shift in focus to formal and informal responses at the community level to address poverty.

One of the ugliest consequences of our modern political debate is that we implicitly delegate caring for people to the government. Debates about what government should do become conflated with debates about what we as people should do, with people on both sides often losing track of the latter. Poverty requires us not to fix a broken system, but to boldly reimagine how the right system might look.