Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has proposed a Green New Deal. The plan would involve “’upgrading all existing buildings’ in the country for energy efficiency; … ‘Overhauling transportation systems’ to reduce emissions — including expanding electric car manufacturing, building ‘charging stations everywhere’ and expanding high-speed rail to ‘a scale where air travel stops becoming necessary’; A guaranteed job ‘with a family-sustaining wage’ … [and] ‘High-quality health care’ for all Americans.” And these efforts won’t come cheap: the program is expected to cost at least $40 trillion in the first 10-15 years.

When asked how her plan would be paid for, Ocasio-Cortez suggested that the wealthy would need to pay income tax rates of 60-70 percent. She also wants to lean on monetary policy. To this end, she cites modern monetary theory, a fashionable economic theory that even Paul Krugman disavows.

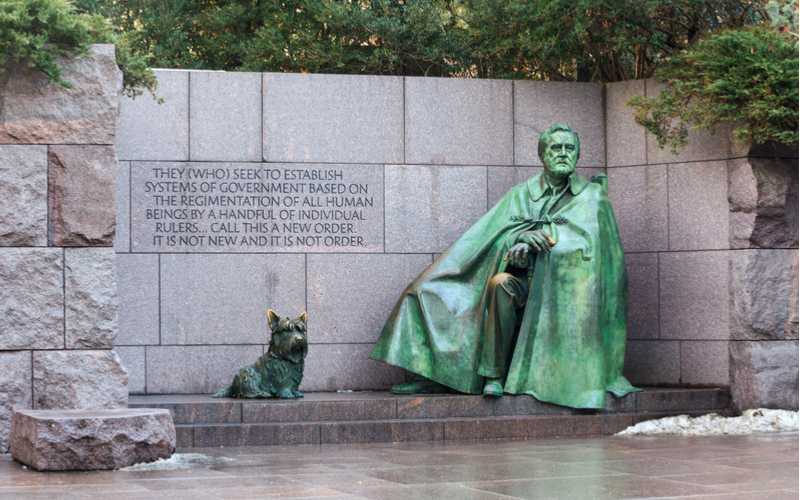

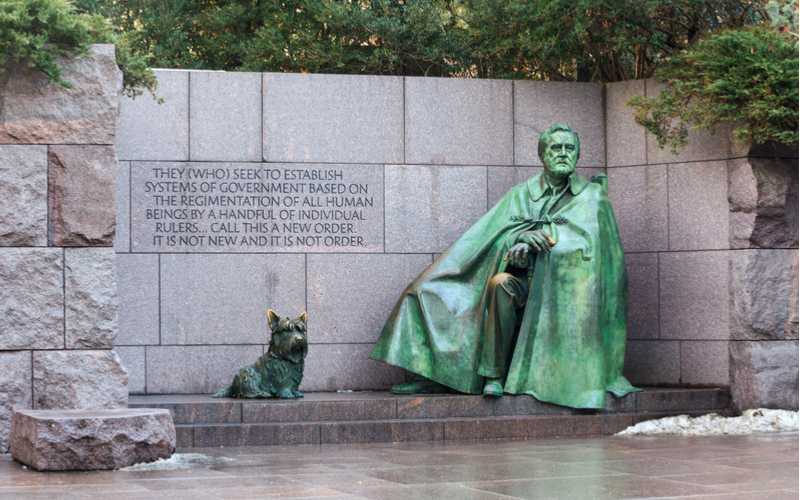

Ocasio-Cortez is simply following in the footsteps of her progressive predecessors. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who pushed the original New Deal, was driven by the belief that his own experimentation was superior to the processes that would otherwise drive economic outcomes. He intervened accordingly.

In his meticulously researched American Default: The Untold Story of FDR, the Supreme Court, and the Battle Over Gold, Sebastian Edwards details the acts and disposition of FDR at the height of the Great Depression. Edwards describes FDR as an “experimenter” (14). This is not simply Edwards’ attribution. President Roosevelt himself argued that “the country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

Roosevelt might have made a great entrepreneur. But, as president, this attitude is downright dangerous. In the political context, “try something” means “make decisions about how wealth should be distributed and how rules concerning wealth should be administered.” Worse still, FDR sought to intervene in an attempt to correct imbalances created by a poorly managed international gold standard.

In seeking to correct the imbalances, the president proposed ideas to his advisors, none of whom were experts on monetary policy. Rexford Tugwell admitted this, writing in his diary that “[w]e were not monetary theorists.… I wondered why he discussed … [monetary policy] with us” (7). This did not stop FDR from attempting to implement myriad policies affecting money; and he was often successful.

Intervening in the Rule of Law

FDR worked to transform the monetary system to align it more with his own vision. He transformed the monetary constitution by ending gold redemption in the first month of his presidency. He devalued the dollar in 1934, making an ounce of gold worth $35 when it had previously been worth $20.67. He also annulled gold clauses in contracts. The rule of law with respect to money was degraded and wealth redistributed from lender to debtor.

We have no reason to believe that FDR and Congress made the decisions that most improved the welfare of U.S. citizens. Other paths may have been taken to yield a similar result without degrading the rule of law. For example, the president could have legalized interstate branch banking to mitigate the banking crisis or pressured Federal Reserve officials to expand in concert with gold inflows. He could have laid the foundation for such policies by working with Herbert Hoover when he was president-elect. While one cannot claim with surety that these policies would have yielded the desired results, it is not difficult to imagine FDR experimenting with policy without experimenting with the rule of law.

Compared to Market Entrepreneurs

Compared to entrepreneurs in a competitive market system, political entrepreneurs are not subject to a process of competition and selection that systematically orients their actions toward an end. In the case of markets, this end is efficient value creation in service of consumers. The constraints and processes that guide market activity naturally transform the efforts of entrepreneurs into benefits for the consumer.

Not only must entrepreneurs provide value, but they must predict future preferences of consumers. Entrepreneurship is fraught with uncertainty. Market entrepreneurs often fail, and this is a good thing. Losing ideas are removed from the marketplace, and winning ideas are rewarded with profit. Those entrepreneurs who feel less inclined to innovate can simply replicate and marginally alter strategies that have already proven effective. This process of competition and selection benefits the consumer, who receives a significant share of the value created by any given entrepreneur.

For a market entrepreneur, a mode of forceful experimentation is a reasonable approach. Without such experimentation from entrepreneurs in the market, technologies may be slow to develop and the creation of value may be inhibited. Entrepreneurs develop and implement new means of serving consumer preferences, whether by providing at lower cost goods that consumers already demand or by providing new goods to consumers.

Entrepreneurs can also create value by offering incentive-compatible solutions to macroeconomic problems. The competitive system generates innovation in finance that can help supplant macroeconomic disequilibrium like the kind experienced during the Great Depression. For example, markets generate liquidity, which tends to promote stability. And private banking systems mitigated moral hazard and generated emergency currency during crises before the Federal Reserve began to operate.

Very often, instability in the market system is the result of a complex set of interventions. This was certainly the case during the Great Depression, when government monopoly over currency and regulation affecting branch banking led to many thousands of banks closing in the United States. In Canada, where the banking system was not subject to the same branching regulations, no banks failed. While I don’t expect that FDR considered deregulation an option, history suggests that it would been a beneficial path forward. And this path would have respected the rule of law.

The Result of FDR’s Political Entrepreneurship

FDR’s political entrepreneurship, on the other hand, represented a massive transfer of wealth from investors to debtors and an abrogation of the rule of law. FDR’s role as a Big Player provided him inordinate influence over market activities. Changes in policy and in rules supposed to constrain policy transform payoffs of economic players across society. Some win, some lose. Who wins and who loses is difficult to predict beforehand. The Supreme Court ruled in 1935 by a slim margin of five to four in favor of sustaining FDR’s abrogation of the gold clause. While one can imagine events turning out differently, reversing the action may have been more damaging.

Two years earlier, Congress and the president had together enacted a program of devaluation that went so far as to alter the terms of past contracts, public and private. The economy had proceeded on this basis. This surely placed pressure on the court to rule in favor of sustaining the abrogation. The court’s decision may also have been influenced by the willingness of the president to exploit his position as a Big Player. In conferring with his advisors, FDR considered promoting economic volatility in the event of a loss before the Supreme Court.

Edwards notes that the court ruled eight to one, arguing that abrogating the gold clause in regard to government debt was unconstitutional, but continued by noting that no damages had occurred and that, therefore, there were no grounds for holders of Liberty Bonds to sue for compensation. The justices disagreed with the president, but not enough to engage in a war that could have damaged American institutions of governance. Though he was browbeaten by the judiciary, FDR’s maneuvering was successful. The gold standard ceased to secure sound money, and the Supreme Court allowed the president and Congress to increase their influence.

The battle over the gold clause was the first of many that FDR would engage in with the court. He eventually threatened to pack the court with enough judges to promote rulings that favored his own policies. Luckily this proved to be outside the bounds of political possibility. Still, FDR set the standard for future progressives who wished to exercise broad powers to mold the world as they think best.