Executive Summary

Despite being touted as a responsible and sophisticated framework for business and investment, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria lack logical cohesion and internal consistency. Conceptually, no reason exists for why the fundamental ideas within the ESG label should correlate with one another. For instance, social criteria regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion often undercut environmental criteria and vice versa. And “good” environmental or social scores can be used to paper over significant governance issues. This makes the ESG label a confusing concept and an incoherent umbrella label under which a wide variety of social, political, economic, and environmental interest groups compete to advance their agendas using the label of “responsible” or “sustainable” investment.

Part of the incoherence of ESG stems from mixing sound business and investment practices with ideological priorities. These new ideological priorities have little to do with successful business performance or high financial returns. Nor are they backed by sound research or substantial evidence. Instead, they are a collection of “just-so” stories glommed onto existing business practices and strategies. Even those who embrace ESG should recognize the value of disaggregating it into its three different components. Evaluating disaggregated environmental, social, and governance categories independently of each other will help companies and investors allocate capital more efficiently and effectively while encouraging more transparent engagement of societal problems.

Key Points

- The acronym “ESG” is not a coherent framework of analysis but rather an umbrella label for a host of often unrelated ideological causes.

- Contradictions between Environmental, Social, and Governance goals abound.

- The Social category has the most ideology and the least connection to company performance and profitability.

- ESG ratings vary widely and often contradict one another – making them poor indicators of financial risk or future business performance.

- Both ESG advocates and ESG skeptics would be better served by disaggregating the “E,” the “S,” and the “G.”

Introduction

This paper contends that using Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) as an umbrella label taints sound business practices and risk analysis with nonfinancial ideological goals and causes. The ESG framework does not contribute anything substantive to running companies profitably. Nor does it provide an effective way of addressing social issues. Furthermore, ESG criteria generate costly, and often garbled, information for investors. We ought to scrap the ESG acronym entirely as a distracting, often ineffective, and inappropriate method for doing business and for investing.

A key shortcoming of ESG lies in the lack of logical coherence between the Environmental, Social, and Governance categories. No clear connection, or even correlation, exists between the “E,” the “S,” and the “G.” As Richard Morrison points out: “ESG means very different things to different people. Some advocates want to advance specific environmental or labor policy outcomes. Some are individual investors who want a competitive rate of return but want to minimize their carbon footprint. Others are professionals looking to sell ESG-themed financial products and consulting services[.]”1 These objectives cannot all be pursued effectively.

The appropriation of reputable business practices and ideas drove ESG’s initial popularity within the business and the investment community. But the ESG label has become a convenient vehicle to advance a whole range of non-financial concerns in corporate governance and in the investment community. Over time, advocates co-opted proven existing risk-related criteria from business and finance and added nonfinancial social and environmental criteria. These new criteria often depart from sound business practices – creating tensions and contradictions for firms with fiduciary duties to shareholders, investors, and clients.

Terrence Keeley, a former Managing Director of ESG investing at Blackrock, has written extensive criticisms of ESG as an investment framework. He points out that ESG investing generally delivers lower financial returns.2 Divesting from “non-ESG” firms does not reduce their customer base or their market or carbon footprint.3 Most ESG criteria reduce motivation and accountability for business executives to create value.4

In addition to these problems, the logical incoherence of ESG criteria often results in high levels of ambiguity, sometimes to the point of meaninglessness. ESG has become, in effect, a large amorphous blob creating costs, distortions, and inefficiencies throughout the economy. It ought to be broken into its distinct categories (E, S, & G) with much closer scrutiny of the ideology embedded in social criteria.

Section Descriptions

Section two explores the incoherence of the ESG label. ESG ratings firms often come to opposite conclusions about the same companies. The high costs of complying with environmental goals undermine social goals of creating equity and inclusion for minorities and the poor. Advocating the pursuit of stakeholder interests undermines accountability in governance. So too does giving human resource departments greater discretion and authority to pursue diversity, equity, and inclusion priorities. The dozens, or even hundreds, of environmental, social, and governance goals cannot be pursued simultaneously.

Section three points out problems created by ESG’s incoherent framework. It highlights several studies that question whether adopting the ESG label leads to better financial or better social outcomes. Although claims that adopting ESG criteria will improve a company’s performance abound, most are little more than “just-so” stories – that is, stories told with little or no evidence. Indeed, evidence that pursuit of ESG harms profitability and rates of return continues to increase.

Section four shows how ESG became a convenient acronym for mixing non-financial ideological goals (often described as “politically correct” or “woke”) with sound business practices. Despite protests to the contrary, many ESG reporting requirements are not material to companies’ financial prospects because they are unrelated to, or even negatively related to, profitability. This especially concerns the “Social” category that typically advances the concerns and goals of progressive activists and government officials. The social category creates economic inefficiency and hinders the advancement of important environmental and governance goals because it foments so much division and political opposition.

Section five concludes with a better path forward: disaggregating ESG and dropping the social category. Breaking ESG into its component parts will provide greater investment clarity. Investors, business executives, and government officials concerned about environmental and governance issues should welcome such a change. Returning to business and investing norms and practices before the development of the “Social” category will also improve financial performance and increase economic growth.

Section II: The Incoherence of the ESG Framework

ESG has often been touted as the future of capitalism.

Its advocates claim that executives, politicians, and investment fund managers who don’t get with the ESG program open themselves to greater risk, public censure, and lower performance. As Deutsche Bank puts it: “ESG investing: once a nice-to-have, now a must-have.”5

CEOs at Fortune 500 companies got the memo and have largely fallen in-line with ESG and its broader stakeholder capitalism roots. Consider, for instance, how the Business Roundtable redefined the purpose of a corporation in 2019. Its “Updated Statement Moves Away from Shareholder Primacy, Includes Commitment to All Stakeholders.”

The signatory CEOs write: “we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders” including customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders.[6] This suggests a real, perhaps an equal, obligation to all stakeholders, whoever they might be. But the signatories make no distinction between contractual stakeholders (customers, employees, and suppliers) and non-contractual stakeholders (such as the “community,” “environment,” or “nature”).

From where does the obligation to non-contractual stakeholders arise? Long-term business success depends on good relationships with all these groups – so why the change in language prioritizing “stakeholders?” Did these companies treat their contractual stakeholders – customers, employees, and suppliers – badly in the past?

These questions were not addressed by the Business Roundtable statement. Nor does that statement have anything to say about the costliness and potential distraction these new commitments create.

Costs created by ESG policy reduce equity

ESG advocates do not adequately address the costs of their net zero agenda. Although they claim to champion “equity” in the social category, burdensome regulations and reporting requirements in the environmental category create significant and uneven costs. For example, the SEC has estimated that compliance costs for its Climate-Related Disclosure rules will be $6.37 billion annually; though some argue the actual cost will be even greater.7

Some of those costs will be borne by investors who see lower returns – which includes pensioners of modest means. But much of the cost will fall on consumers in the form of fewer options and higher prices. Although higher prices are on people’s minds because of the recent spike in inflation created by loose monetary policy in 2020 and 2021, ESG advocates rarely mention how many of their recommendations ultimately increase prices and, in doing so, disparately impact the poor – including many minority communities. McKinsey & Company, for example, estimates the global transition to net zero by 2050 will cost $275 trillion dollars. 8

Implementing environmental policies like more stringent limits on vehicle or power plant emissions, reducing carbon footprints by purchasing carbon offsets, or mandating more renewable energy use, increases the cost of doing business. Electricity and gasoline prices in the state that has done this the most – California – are much higher than in other parts of the country. The retail price of electricity in California is about 29 cents per kilowatt-hour while more than half the other states have a retail electricity price under 15 cents per kilowatt-hour.9 The average price of gasoline in California is $5/gallon while the average U. S. price is about $3.50/gallon.10

These elevated prices, especially as they grow over time, will significantly impact people’s quality of life. The Wall Street Journal ran a news piece about the impact of high electricity prices on Californians living in Borrego Springs. One resident saw her electricity bill exceed $1800 in one month – fifty percent higher than the rent she pays for her house. Similarly, the proprietor of a small grocery store said his monthly electricity bills averaged around $8000 a month, nearly equal to the monthly rent he pays.11

It is not harder to get electricity or gasoline to California. In the name of protecting the environment, the Californian government has implemented policies and taxes that make electricity and gas far more expensive. Similarly, the cost of electricity for at least seven European countries (including Germany and the United Kingdom) are more than double the average cost of electricity in the United States – even as the average cost of electricity in the United States is about twice that of China.12 The higher cost of electricity has a greater impact on the poor than on the wealthy.

Price increases due to environmental regulation extend beyond gas and electricity prices. Ever stricter emissions and miles-per-gallon requirements (CAFÉ standards) make cars far more expensive than they would otherwise be. Food prices rise as ESG policies restrict the types of fertilizer and equipment farmers can use. A recent report conservatively estimates that farming costs will increase by a third, in real terms, should the U. S. implement a net-zero carbon regime.13 These rising energy costs will in turn affect the costs of building houses, apartments, roads, trains, airplanes, clothing, furniture, and nearly every kind of good – because manufacturing and transportation require energy.

ESG advocates want Europe’s and California’s energy policies to proliferate on a global scale. But how is that fair to those living in poor countries for whom easy access to raw minerals and natural gas reserves is critical for their economic development? Should they be denied the opportunity for development enjoyed by wealthier countries had because those same wealthy nations have decided that everyone must reduce their greenhouse gas emissions? The same questions can be asked about states within the U. S. that have different industries, different demographics, and different economic challenges.

How does that square with Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) values? Economies with higher prices are not “inclusive” – far from it! The costliness of these things may have little consequence for highly paid professionals and bureaucrats – the ones most stridently advocating for ESG priorities – but it severely hinders the poor from finding good job opportunities, pursuing further education, and putting their children in good schools or in enriching extracurricular activities.

We can see this inequity in the most pressing problems faced by poorer people: expensive food, expensive housing, and expensive transportation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Expenditure Survey shows that the poor spend greater proportions of their income on food, housing, and utilities than the middle class or the wealthy do.14 Increasing the price of those staples through more red tape and ineffective emissions restrictions will only worsen that phenomenon.

Some ESG advocates claim that more government welfare programs can address these problems – subsidized housing, subsidized education, free government programming, and other transfer payments. Yet these kinds of programs tend to reward consumption and discourage saving and investment. This does little to increase inclusion or equity over time. The income dynamics of welfare also discourage work, encourage dependency, and ensnare people in the “safety net.”15 We can’t wave the magic wand of government programs to fix higher prices, inefficiency, and the disparate impact on the poor that arise from pursuing environmentalist dreams.

Pursuing DEI Priorities Requires Unjust Discrimination

Within the social dimension of ESG, the concepts of equity and diversity run into internal inconsistency. Both concepts can be weaponized. For example, what counts as “diversity?” Is it the color of one’s skin? Or where one’s parents are from? Or how one “identifies” their sexual orientation? Or what political party one supports? “Diversity” requirements can easily be co-opted by ideological commitments and beliefs. Ironically, those in positions of authority gain more power and less accountability through DEI programs because they have additional tools for exercising their preferences.

Promoting greater discrimination in hiring on the basis of racial categories cuts against the whole idea of inclusion and intersectionality. Part of the “logic” of these values is to empower those who have little or no power. DEI purports to do this by giving more power to the “right” kinds of people to advance the interests of various “oppressed” groups – yet it doesn’t actually protect anyone from unfair discrimination.

The Supreme Court made exactly this point in Students for Fair Admission v. Harvard.16 Harvard’s admissions policies did not treat applicants equally. The university’s attempt to advance DEI actually reduced diversity by admitting fewer Asian applicants on the basis of their ethnicity. The DEI admissions policies gave staff more power to “right” alleged injustices or social wrongs. Yet the policies proved to be inherently racist and discriminatory by reducing the inclusion of students of Asian descent who were otherwise qualified, save for their ethnicity.

Similar problems emerge when incorporating DEI into human resource teams or corporate governance structures. Pushing DEI priorities within organizations reduces accountability for HR departments and hiring managers. More specifically, they are given greater discretion in hiring (and firing) because they can use DEI related criteria to justify exercising their own personal preferences and prejudices. Supposedly inclusive policies lead directly to exclusion and persecution of people who do not agree with or do not fit the beliefs and agendas of those who wield the power to define “equity,” “diversity,” and “inclusion.”17

Weighting ESG Scores Involves Subjective Matters of Opinion

What do people get when they invest in “ESG?” Less emissions? More diversity? More reporting? Higher wages? Less pollution? Unfortunately, ESG ratings could involve any or all those things to varying degrees. But there are also mutually exclusive ESG criteria.

Terrance Keeley describes some of the problems that emerge from treating the “E,” the “S,” and the “G” together in his book Sustainable:

thoughtful investors and financial advisers must segment “E,” “S,” and “G” risks and opportunities….[averaging] excellent “S” and “G” but problematic “E” scores….often masks how potentially devastating specific “E” exposures may be….Similarly, debilitating “G” concerns could overwhelm positive “E” and “S” attributes….In the interests of all sides, it may be best for “E,” “S,” and “G” to divorce. Their relationship appears irreconcilable.18

Analysts and investors cannot simply average E, S, & G scores. They are often totally incommensurate with each other.

The incoherence of ESG can be seen in its inconsistent rating of companies. While ESG scores for the same company can vary widely based on the outfit doing the assessment, traditional credit scoring has far less variation even when done by different agencies.19 Consider how the ESG scoring of PepsiCo, Inc. and Coca-Cola Co. by two of the most sophisticated ESG rating firms varied dramatically.

In 2021, MSCI rated Coca-Cola AAA in their ESG scoring but they rated PepsiCo AA. Sustainalytics, on the other hand, gave PepsiCo a low-risk score of 16.0 while they gave Coca-Cola a medium-risk score of 22.5 – with low scores being better than high scores – all based on ESG factors!20 These companies are not in different industries. They should be an apples-to-apples comparison – yet the subjective elements of ESG scoring led to significant disagreement.

Or consider how in May 2022 Exxon Mobil was scored more favorably and included in the S&P 500 ESG Index while Tesla – the pioneering electric vehicle company – was dropped from the index. The argument put forward at the time was that Tesla fell into the bottom quarter of its “industry group peers.”21

Although scoring well on some environmental factors, Tesla was penalized for lacking an explicit low-carbon strategy document. On the social and governance fronts, S&P highlighted two events involving claims of racial discrimination and poor working conditions. They also said that several crashes had been “linked” to Tesla’s autopilot system.22 The idea that documentation matters more than a company’s actual track record has been found in other studies.23

This episode highlights the tensions and contradictions within the ESG label. Tesla clearly outperforms Exxon Mobil when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions. Yet the company was excluded from an ESG index for not checking the right boxes and for subjective evaluations of “other risk factors.” People investing in ESG-labelled funds because they care about climate change would presumably be shocked to learn they were holding Exxon Mobil in their portfolio but not Tesla.

Finally, consider how problematic Sustainalytics ESG rating of Fisker in May 2024 was. They gave Fisker a “Medium Risk” ESG score of 25.1, quite similar to Tesla’s “Medium Risk” ESG score of 24.7. Less than a month later (June 18, 2024) Fisker, Inc. declared bankruptcy. If ESG is a framework for assessing risk, it is clearly flawed if it misses imminent bankruptcy and gives a failing electric vehicle manufacturer a similar risk profile as the most valuable vehicle manufacturer in the world.

ESG advocates also tend to turn a blind eye to poor governance when a company has the right DEI stances and favorable language on other ESG issues. Corporate governance at Meta and Alphabet, for example, can hardly be called independent or accountable. At Alphabet, Larry Page and Sergei Brin have most of the voting rights even though they own less than twelve percent of the company. For Meta, Mark Zuckerberg has more than half the voting rights but owns less than fifteen percent of the company. These massive influential companies are governed by the beliefs and goals of just a few individuals rather than the majority of their shareholders.

How is this inclusive? Or even a best practice when it comes to making good corporate governance decisions? This is less, rather than more, stakeholder representation. Yet these companies score highly on ESG because they don’t produce or use as many emissions as other industries do, they have made various net zero commitments (as opposed to tangible progress), and they have extensive DEI divisions.

This represents merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the contradictions and wastefulness of most ESG criteria. Yet many different people have strong interests in sailing ESG full-steam ahead: financial advisers, consultants, and green energy companies that collect billions of dollars through ESG-related activity; legislators and government bureaucrats who use ESG to justify expanding their authority and power; and the thousands of people working at international NGOs, nonprofits, and UN-related organizations whose livelihood depends on ESG evaluation and adoption; not to mention the powerful elites who want to radically reshape the global economy.

Section III: Economic Problems Emerging from ESG’s Incoherence

The deep and pervasive disagreements in the U.S. about ESG suggest that it is not solely, or perhaps even primarily, about improving business performance. While ESG advocates are happy to use government to promote and enforce their ideas, many of their objectives are progressive political goals rather than scientific, economic, or financial improvements.

The most obvious reason to suspect the business merits of ESG is that most corporate executives must be pressured to use it. If ESG criteria improved their company’s performance and profitability, executives would naturally want to incorporate it into their management. Instead, we see groups of ESG advocates in nonprofits, consulting, and investment circles actively pressing companies to expand their ESG analysis – while many of the executives in the company are lukewarm or hostile because they don’t believe many of these ESG criteria are necessary or helpful in running their companies.

ESG advocates often assert that there will be economic benefits and lower risks when companies pursue net zero or more DEI or a better “social license to operate.” Yet many scholars argue that implementing ESG does not reduce risk or improve performance, financial or otherwise. Raghunandan & Rajgopal, for example, found that investment funds labelled “ESG” did not correlate with better stakeholder outcomes as measured by violations of health, safety, and other regulations.24 These ESG funds also did not invest in companies with smaller carbon footprints. Instead, the authors found that high ESG scores correlate with “the existence and quantity of voluntary disclosure…but not with the actual content of such disclosures.”25

The authors also found that, in most cases, the funds’ prospectuses and websites “explicitly consider ESG-related issues as reasons to invest in, avoid, or divest from individual stocks, without citing the potential financial consequences of those firms’ ESG issues as a reason for picking or avoiding them.”26 What seems to matter when it comes to ESG funds is not whether or how firms use ESG criteria to improve their financial outlook, but rather how well they check the formal pro-ESG boxes created by a variety of ratings agencies.27

This raises significant problems for investing using ESG metrics to evaluate which companies are better investments. ESG advocates simply assume more information is better than less – without acknowledging the significant costs of collecting certain information. Nor do they recognize that most ESG-related information muddies the waters instead of improving clarity.

Similarly, Gibson et al. show rampant “greenwashing” in the U.S.28 That is, they find that the portfolios of institutional investors committing to ESG by signing onto the Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI) initiative do not have higher ESG scores than the portfolios of institutional investors who did not sign the PRI initiative. And institutional investors that signed the PRI initiative but did not report any effort to comply had significantly lower ESG scores in their portfolio than non-signatories. This suggests that significant ESG investment amounts to virtue-signaling support for ESG rather than substantive behavioral change.

In another study, the University of Chicago’s Hartzmark and Sussman analyzed investment flows and returns based on Morningstar’s “globe” rating regarding sustainability.29 While they found that high sustainability ratings led to greater capital inflows and low ratings led to capital outflows. They also discovered that higher sustainability scores did not lead to higher financial returns.

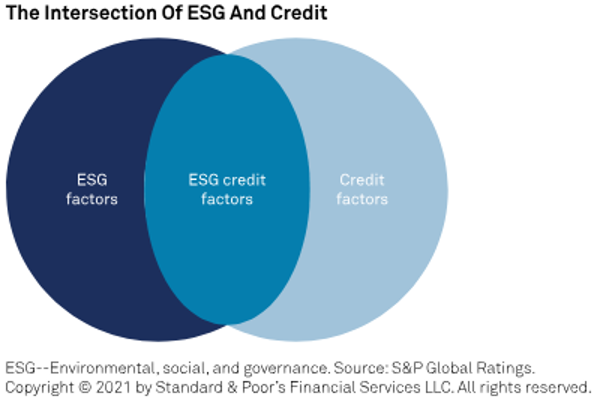

Consider how S&P Global, itself a major proponent of ESG, distinguishes between ESG credit factors and ESG non-credit factors – admitting that only some ESG criteria matter for a company’s creditworthiness (Figure 1).

Figure 1

This raises an obvious question: what value does the ESG circle bring when the credit factors circle contains all relevant information for determining creditworthiness? As the ESG label has become more widespread and all-encompassing, business faculty and business schools have become more hesitant to criticize it. Many embrace ESG because it opens new vistas for research, consulting, specialization, and building careers. ESG-related roles have also proliferated, increasing student demand for ESG content in their programs at business schools.

All the top business schools have extensive ESG programs and research. At Stanford, many of its science departments have been reorganized into the Doerr School of Sustainability. Wharton has added new MBA programs: “Environmental, Social, and Governance Factors for Business” and “Social and Governmental Factors for Business.” It also renamed its Risk Management and Decision Processes Center the “Climate Center.”

The Kellogg School of Management has many “pathways” for its students to follow including: “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” “Sustainability: Climate, Environment, and Energy,” and “Sustainability: Social Impact and Responsible Leadership.” The Sloan School of Management’s Climate Policy Center has various objectives known as “Climate Missions” all pulled out of ESG criteria. Similar policies and centers exist at Harvard, New York University, University of Chicago, and other elite business schools across the country.

Consultants like ESG because it creates more consulting opportunities. Asset managers like ESG because they can create more funds with higher fees. Corporate managers buy into ESG because it makes them less responsible to shareholders and, frequently, to consumers. Elevating the claims of numerous stakeholders using ESG shifts power from shareholders to boards and company management.

People often use the language of “stakeholder” to justify business practices that pursue social or political goals unrelated, or opposed, to shareholder interests. For example, considering “goodwill” in a community makes business sense in terms of brand, reputation, recruiting workers, and navigating political and regulatory landmines. This contributes to long-term profitability. But labelling these groups as “stakeholders” and advocating that companies be run in their interest and for their benefit will undermine long-term profitability.

Claims that ESG contributes to a company’s bottom line or improves the environment are often little more than just-so stories. While advocates claim clear connections between ESG criteria and desirable results, they generally have little or no evidence supporting their claim – it is “just-so.” Of course, isolating and measuring the effects of specific policies is difficult. Still, instead of recognizing such difficulties and the paucity of evidence, most ESG advocates simply assume their criteria are beneficial and stridently work to enshrine them into regulatory and legal frameworks while also pressuring companies to adopt them.

One common story says that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) improve corporate performance. McKinsey & Company released a study in 2015 arguing that there was a positive relationship between diversity among company executives and that company’s “industry-adjusted earnings before interest and tax margins.”30 They have released subsequent publications continuing to make this case.31 The publications bolstered their consulting pitch to help companies polish their DEI bona fides – yet their evidence is poor.

A recent study by Jeremiah Green and John R. M. Hand examined these McKinsey articles and attempted to replicate their results. Instead of reproducing the results, they found no evidence that board diversity was even associated with better performance, let alone the cause of better performance.32 Their study included a broader set of data than the McKinsey studies – which means they used a more representative sample, reducing the risk of cherry-picking.

Similarly, claims about the high intangible value of companies are part of the founding of ESG: “ESG issues can have a strong impact on reputation and brands, an increasingly important part of company value. It is not uncommon that intangible assets, including reputation and brands, represent over two-thirds of total market value of a listed company.”33 ESG advocates say this high intangible value justifies greater use of ESG criteria because it helps companies build a valuable brand, reputation, and goodwill.

Yet the growth of intangible value in business enterprises arises from the shift towards information and services and away from manufacturing. For example, U. S. Steel’s intangible value will be far less than Alphabet’s because the former makes money by using significant fixed assets to generate physical output while the latter generates significant services with a relatively small physical footprint.

But consider how “goodwill” or “intangibles” are used under the ESG label. When it comes to Social or Governance criteria, ESG advocates argue for a “social license to operate” concept that would require companies to have specific kinds of social appeal, or rather the approval of certain social groups – again, generally those groups identified by progressives as deserving special status in society.

In this formulation, concern for business reputation as it relates to profitability turns into a kind of extortion racket where companies can improve their official social score (according to highly progressive ESG rating organizations) by doling out money or favors to vocal special interest groups – most of whom are of the progressive variety.

Yet intangible value primarily stems from a superior ability to:

- create new products

- build and maintain goodwill and customer loyalty

- assess and mitigate risk

- reduce regulatory burden

- avoid potential legal liability

How valuable is a “green” brand or an LGBTQ+ brand? How would one measure such value? What about other constituencies deterred by that brand? ESG rating agencies disagree with one another about how to weight competing social issues or branding. What’s more, why rate companies according to a few highly contested issues in the “S” category when a multitude of factors matter? Firms in a competitive marketplace should decide such things, not regulators, analysts, or pundits.34

Section IV: Jettisoning the Inefficient and Divisive “Social” Category

Is ESG about increasing value for shareholders or is it about advancing social and political goals? The origins of the ESG framework in the corporate social responsibility movement and international development community suggest the latter.35 Advocates label many traditional business tools and practices “ESG,” even though the label does no analytical work. In the process, progressive, non-financial criteria, goals, and expectations, which often detract from profitability, worked their way into the label.

The authors of the 2004 “Who Cares Wins” UN report and subsequent ESG advocates recommend that businesses extend their time horizons to twenty years, fifty years, and even one hundred years. But extending the time horizon dramatically increases uncertainty. This necessarily generates conjecture and little real information. Companies should only be required to report data that are “reasonably estimable.” Requiring companies to provide guidance and forecasts for their business and the state of the world ten or more years in the future does not meet that standard.

The initial ESG criteria highlighted in that 2004 UN report are reasonable, if ambiguous, business concerns such as “the need to reduce toxic releases and waste,” “workplace health and safety,” “community relations,” “board structure and accountability,” and “management of corruption and bribery issues.”36

All these criteria, however, mattered before the ESG label was created. The report failed to explain how all these factors correlate with and reinforce one another. By importing a variety of historical risk management terms and business management practices, and couching ESG in terms of shareholder primacy, ESG advocates have successfully enlisted business faculty, consultants, and asset managers to support their invariably progressive political agendas. Yet it has become abundantly clear that many ESG advocates simultaneously try to undermine shareholder primacy.37

Yet U. S. corporate law enshrines shareholder primacy.38 The corresponding fiduciary responsibility of boards of directors and company managers to advance the long-term interest of shareholders creates problems for the ESG label – especially as it has become less and less connected to profitability.39

In the corporate board room, another just-so story goes, having more diversity in the form of more women or more minority board members will help the company make better decisions. Advocates claim that:

- Diversity helps boards avoid “group-think” because diverse board members have different backgrounds, beliefs, and perspectives that will prevent them from just going along with the majority.

- Diversity brings more knowledge to bear in corporate decisions because women and members of minority groups presumably have different lived experiences, knowledge, and perspective.

- Diversity on the board might help a company reach more customers who can relate to minority communities better. Serving more stakeholder interests could improve a business’s reputation and reduce its future legal liability.

Yet none of these claims has been shown to be true. Sure, boards that don’t consider many alternatives or don’t examine their strategies critically are more likely to make costly mistakes. But do we know that having more women or minorities on the board will change this? And how would we determine this, especially considering the questions now surrounding the McKinsey study that advanced this thesis? Many firms that were already successful have increased their diversity as a defensive measure against unfavorable regulatory or financing.

Perhaps such DEI candidates will often go along with the majority out of peer pressure. Or maybe they will tend to agree with the majority because they happen to hold similar beliefs and ideals, despite seeming to have different backgrounds. And why assume that different ethnic or gender backgrounds automatically translate into different views? Maybe their backgrounds won’t be all that different.

Similarly, the generalization that more “diverse” board members will bring better knowledge to the table also falls flat. This could happen, but it might not. After all, what knowledge is truly important for making good corporate governance decisions? Is it primarily knowledge of one’s own idiosyncratic upbringing and social context? Or is it the ability to assess market trends, legal liabilities, technological change, revenue and cost dynamics, and capital markets? Children would increase the “diversity” of a corporate board, but that doesn’t mean the board would then make better decisions.

Having more diverse board members might help a company figure out how to access more niche demographics, but it might not. More importantly, there are many other ways to gain such information than adding certain people to a corporate board. Consultants, market research, and consumer surveys are all means to learn about an unfamiliar market. “Serving” broader stakeholder groups, presumably represented by more “diverse” board members, may or may not improve a business’ reputation.

Yet, despite the highly speculative nature of these claims, major investment institutions push companies to adopt these practices.40 The shareholder proxy advisory services, Institutional Shareholder Services and Glass-Lewis, have ethnic and gender diversity standards for boards.41 Similarly, the Nasdaq stock exchange began requiring companies to have at least one woman on the board before they can be listed on the exchange.42

Given the scale of these problems, we should not be surprised that not only do those outside the ESG movement recognize these fundamental inconsistencies and contradictions. Even a few ESG insiders recognize it. Growing awareness of these inconsistencies and contradictions explain why many companies have begun scaling back their ESG initiatives – especially their DEI programs.43

Evidence that DEI and other social criteria cut against profitability while stoking heated disagreement continues to mount. Besides the significant backlash seen in high-profile cases of Disney, Target, and Anheuser Busch, including noteworthy declines in their enterprise values, 2024 has seen a wave of companies dismantle and abandon their DEI-related initiatives: Harley Davidson, Tractor Supply Co., John Deere, Ford, Lowes, and more.

Activist investor Robby Starbuck has been publicly making the case that DEI quotas, trainings, and priorities have been reducing company performance. So too does reporting to and attempting to comply with the Corporate Equality Index created by the Human Rights Campaign. Some CEOs, like Brian Armstrong at Coinbase, proactively sought to avoid these issues by issuing memos to employees to focus on work and leave political and social crusades out of their work.44

The just-so stories about the benefits of DEI or other social criteria may hold true in some situations but certainly haven’t held true in many others. Determining when they apply requires judgment and context, not uniformity or dogmatic quotas. The decision about who should serve on boards should be left to the discretion of those with the most knowledge and the best incentives to make a value-adding decision: current management, board members, and shareholders.

Section V: A Better Path Forward: Disaggregating ESG

ESG fails on its own proffered terms. It has no unified standard or set of recommendations. Many of its criteria directly contradict each other. Diversity, equity, and inclusion requirements require discrimination. Racial and gender quotas mean sometimes not getting the best board or management candidates. Net zero goals create massive costs, especially for the poor. ESG indices and ratings tend to reward companies for measuring ESG criteria rather than for implementing ESG criteria. Furthermore, these ratings vary widely based upon the subjective evaluations of analysts.

The explosion of corporate “social” activism in 2020 fomented widespread resentment and significant opposition to ESG across the United States. The rebirth of virulent political correctness and the spread of “wokeness” in corporate America alienated customers and large numbers of the workforce.

High profile examples include the feud between Disney and the Florida government and Target’s and Anheuser Busch’s aggressive pushing of LGBTQ products or marketing upon customers. These companies paid a price in terms of market share and revenue for pushing social criteria unrelated to their business model, their customer base, and their long-term profitability.

A wave of large U. S. companies from Ford to Lowes to Coors to Tractor Supply have decided the best way to operate successfully and improve shareholder returns is to stop pursuing social criteria like DEI initiatives. Their ESG ratings will no doubt decline, but that may not matter if the ratings are flawed and inconsistent anyway.

More broadly, the widespread pushing of social criteria by the ESG movement has also created significant political backlash as state legislators and state attorney generals have become concerned about the financial implications of ESG for their pension and retirement funds. The ideological basis of the social category, without any connection to profitability, calls into question the entire ESG movement. ESG advocates would be wise to drop the social category altogether if they want to make progress on environmental or governance issues.

It is time to disaggregate Environmental, Social, and Governance criteria. The internal problems of the ESG label suggest many avenues for reform. The financial industry created most of the ESG mess – from writing the Who Cares Wins UN Report to pushing ESG reporting and disclosure through proxy firms – so many reforms should start there.

Strengthening and clarifying fiduciary duties of boards, corporate executives, and asset managers will require them to prioritize the financial wellbeing of their companies and clients. Requiring more ESG disclaimers for funds that invest in ESG – whether that be asset managers offering ESG funds or the directors of large pension funds allocating part of their portfolios to ESG causes – will provide greater transparency.45

Business schools that have boarded the ESG Titanic should get off before it sinks. ESG is not a framework for good business practices. Nor is it a compelling approach to addressing social problems. Business faculty should resist pressure to teach ESG because of its status in some elite circles. Although there is a lot of energy around buzzwords like “sustainability,” “climate,” and “social responsibility,” these schools will serve their students better by teaching them hard management and accounting skills rather than how to cross ESG t’s, dot ESG i’s, and push ESG paper – activities that generate little value for society but significant revenue for consultants and lawyers.

Society would also be better served if regulators refused to use ESG criteria and only focused on legal and fiduciary matters. Internal contradictions and the lack of clear standards and measurement of ESG criteria mean such regulations will be ambiguous and costly to comply with. ESG mandates will also reward form over substance. Ambiguous regulations can be weaponized to advance the values and goals of regulators, not the public good.

If regulators have a compelling reason to focus on an environmental, social, or governance issue, they should do so directly without bundling them together. There is no value added from aggregating them. If anything, the use of ESG as an umbrella term makes it more difficult for firms to provide a faithful representation of their accounting and business practices.

Ultimately, we should disaggregate the ESG label and jettison the Social category altogether. Governance and Environmental concerns can then be addressed directly without the ideological baggage of DEI, “license to operate,” “intersectionality,” and the like. Proposals to subsidize renewable energy, restrict greenhouse gas emissions, or set net zero targets would have to stand or fall on their own merits without being rolled into a broader ideological agenda. Advocates would have to articulate how each of their criteria advances the interest of shareholders, pensioners, and investors.

Breaking apart the ESG moniker will allow investors, regulators, and corporate executives to refocus their attention on substantive business matters while leaving social and political matters to be addressed in the public square. C. S. Lewis once wrote,

“But progress means getting nearer to the place you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning, then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road; and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man….There is nothing progressive about being pig headed and refusing to admit a mistake….Going back is the quickest way on.46

That aptly describes what ought to be done when it comes to ESG.

Endnotes

[1] Morrison, Richard. “Environmental, Social, and Governance Theory: Defusing a major threat to shareholder rights.” Competitive Enterprise Institute, 2021. https://cei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Richard-Morrison-ESG-Theory.pdf.

[2] Keeley, Terrence. “ESG Does Neither Much Good nor Very Well.” Wall Street Journal, September 12, 2022. https://www.wsj.com/articles/esg-does-neither-much-good-nor-very-well-evidence-composite-scores-impact-reports-strategy-jay-clayton-rating-agents-11663006833.

[3] Keeley, Terrence. Sustainable: Moving beyond ESG to impact investing. New York: Columbia University Press, 2022.

[4] Gramm, Phil, and Terrence Keeley. “Ending Environmental, Social, and Governance Investing and Restoring the Economic Enlightenment,” American Enterprise Institute, December 19, 2023. https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/ending-environmental-social-and-governance-investing-and-restoring-the-economic-enlightenment/.

[5] Deutsche Bank. “ESG Investing: Once a Nice-to-Have, Now a Must-Have and a ‘Huge Opportunity.’” Deutsche Bank, March 17, 2021. https://www.db.com/news/detail/20210318-esg-investing-once-a-nice-to-have-now-a-must-have-and-a-huge-opportunity

[6] “Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘An Economy That Serves All Americans.’” Business Roundtable, August 19, 2019. Business Roundtable. https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans.

[7] Winden, Matthew. “The Unconsidered Costs of the SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rule.” U. S. Securities and exchange Commission, June 17, 2022. https://www.sec.gov/comments/s7-10-22/s71022-20132304-302836.pdf.

[8] Goshen, Zohar, Assaf Hamdani, and Alex Raskolnikov, Alex. “Poor ESG: Regressive Effects of Climate Stewardship,” February 1, 2024. European Corporate Governance Institute – Law Working Paper No. 764/2024, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4771137; McKinsey & Company. “The Net-Zero Transition.” McKinsey & Company, January 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/the-net-zero-transition-what-it-would-cost-what-it-could-bring

[9] Simms, Dan. “Electricity Rates by State (September 2024).” USA Today, September 17, 2024. https://www.usatoday.com/money/homefront/deregulated-energy/electricity-rates-by-state/

[10] AAA. “State Gas Price Averages.” AAA Gas Prices. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://gasprices.aaa.com/state-gas-price-averages/.

[11] Dvorak, Phred. “Why Californians Have Some of the Highest Power Bills in the U.S.” Wall Street Journal, August 5, 2024. https://www.wsj.com/business/energy-oil/why-californians-have-some-of-the-highest-power-bills-in-the-u-s-a831b60e.

[12] Statista. “Electricity Price by Country 2023.” Statista. Accessed June 5, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/263492/electricity-prices-in-selected-countries/.

[13] Lewis, Trevor W, and M. Ankith Reddy. “Net-Zero Climate-Control Policies Will Fail the Farm.” The Buckeye Institute, February 7, 2024. https://www.buckeyeinstitute.org/library/docLib/2024-02-07-Net-Zero-Climate-Control-Policies-Will-Fail-the-Farm-policy-report.pdf

[14] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Table 1101. Quintiles of income before taxes.” Consumer Expenditure Surveys, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables/calendar-year/mean-item-share-average-standard-error/cu-income-quintiles-before-taxes-2022.pdf

[15] Dolan, Ed. “Work Disincentives Hit the Near-Poor Hardest. Why and What to Do about It.” Niskanen Center, May 5, 2022. https://www.niskanencenter.org/work-disincentives-hit-the-near-poor-hardest-why-and-what-to-do-about-it/.

[16] Supreme Court of the United States. “Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College.” Supreme Court of the United States Slip Opinion no. 20-1199, October 2022. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf

[17] Villarreal, Daniel. “Company Ordered to Pay $10 Million for Firing White Man in Diversity Push.” Newsweek, October 28, 2021. https://www.newsweek.com/company-ordered-pay-10-million-firing-white-man-wont-change-diversity-drive-1643697

[18] Keeley, Sustainable, 92-93.

[19] Ibid, 116.

[20] Ibid, 111-114.

[21] Norton, Leslie P., and Ruth Saldanha. “Here Is Why Tesla’s ESG Risk Rating Isn’t That Great.” Morningstar, May 19, 2022. https://www.morningstar.com/sustainable-investing/here-is-why-teslas-esg-risk-rating-isnt-that-great.

[22] Kerber, Ross, and Hyunjoo Jin. “Tesla Cut from S&P 500 ESG Index, and Elon Musk Tweets His Fury.” Reuters, May 19, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/tesla-removed-sp-500-esg-index-autopilot-discrimination-concerns-2022-05-18/

[23] Raghunandan, Aneesh and Shiva Rajgopal. “Do ESG Funds Make Stakeholder-Friendly investments?” Review of Accounting Studies 27, no. 3 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09693-1; Bhagat, Sanjai. “An Inconvenient Truth About ESG Investing.” Harvard Business Review. March 31, 2022. https://hbr.org/2022/03/an-inconvenient-truth-about-esg-investing.

[24] Raghunandan, Aneesh and Shiva Rajgopal. “Do ESG Funds Make Stakeholder-Friendly

investments?” Review of Accounting Studies 27, no. 3 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-022-09693-1, 825.

[25]Ibid.

[26] Ibid, 826.

[27] Such ratings agencies include S&P Global, MSCI, Sustainalytics, Morningstar, and many others.

[28] Gibson, Rajna, Simon Glossner, Philipp Krueger, Pedro Matos, and Tom Steffen. “Do responsible investors invest responsibly?” Review of Finance 26, no. 6, 2022: 1389-1432. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfac064

[29] Hartzmark, Samuel M., and Abigail B. Sussman. “Do investors value sustainability? A natural experiment examining ranking and fund flows.” The Journal of Finance 74, no. 6 2019.

[30] Green, Jeremiah, and John RM Hand. “McKinsey’s Diversity Matters/Delivers/WINS Results Revisited.” Econ Journal Watch 21, no. 1 2024., 5.

[31] Hunt, Vivian, Dennis Layton, and Sara Prince. “Diversity Matters.” McKinsey & Company, February 2015. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business functions/people and organizational performance/our insights/why diversity matters/diversity matters.pdf.; Hunt, Vivian, Lareina Yee, Sara Prince, and Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle. “Delivering through Diversity.” McKinsey & Company, January 2018. https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity. ; Hunt, Vivian, Kevin Dolan, Sara Prince, and Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle. “Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters.”. McKinsey & Company, May 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/diversity%20and%20inclusion/diversity%20wins%20how%20inclusion%20matters/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters-vf.pdf. ; Hunt, Vivian, Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle, Celia Huber, Maria del Mar Martinez Marquez, Sara Prince, and Ashley Thomas. “Diversity Matters Even More: The Case for Holistic Impact.” McKinsey & Company, December 5, 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-matters-even-more-the-case-for-holistic-impact.

[32] Green, Jeremiah, and John RM Hand. “McKinsey’s Diversity Matters/Delivers/WINS Results Revisited.” Econ Journal Watch 21, no. 1 2024.

[33] United Nations Environmental Program Finance Initiative. “Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World.” United Nations Environmental Program Finance Initiative, 2004. https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/events/2004/stocks/who_cares_wins_global_compact_2004.pdf. , 9.

[34] Mendenhall, Allen and Daniel Sutter. “ESG Investing: Government Push or Market Pull?” Santa Clara Journal of International Law 22, no. 2 2024. https://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1261&context=scujil

[35] Morrison, Richard. “Environmental, Social, and Governance Theory: Defusing a major threat to shareholder rights.” Competitive Enterprise Institute, 2021. https://cei.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Richard-Morrison-ESG-Theory.pdf. ; Mueller, Paul. “The Threats Posed by Environmental, Social, and Governance Policies.” American Institute for Economic Research, July 12, 2024. https://www.aier.org/article/the-threats-posed-by-environmental-social-and-governance-policies/.

[36] United Nations Environmental Program Finance Initiative. “Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World.” United Nations Environmental Program Finance Initiative, 2004. https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/events/2004/stocks/who_cares_wins_global_compact_2004.pdf. , 9.

[37] For example, organizations like As You Sow, Strout and the World Economic Forum explicitly say they want to jettison shareholder capitalism.

[38] Bainbridge, Stephen M. The profit motive: Defending shareholder value maximization. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Sharfman, Bernard S. “Now Is the Time to Designate Proxy Advisors as Fiduciaries under ERISA.” Stanford Journal of Law, Business & Finance 25, no. 1 2020. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2443648997/fulltextPDF/D183CD90B1F24DC2PQ/1?accountid=8012&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals ; Copeland, James R., David F. Larcker, and Brian Tayan. “Proxy Advisory Firms: Empirical Evidence and the Case for Reform.” Manhattan Institute, May 2018. https://manhattan.institute/article/proxy-advisory-firms-empirical-evidence-and-the-case-for-reform.

[41] Institutional Shareholder Services. “United States – Proxy Voting Guidelines,.” ISS, January 2024. https://www.issgovernance.com/file/policy/active/americas/US-Voting-Guidelines.pdf , 12; Glass Lewis. “2024 Benchmark Policy Guidelines – United States.” Glass Lewis, 2024. https://www.glasslewis.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2024-US-Benchmark-Policy-Guidelines-Glass-Lewis.pdf.

[42] Nasdaq. “Rules: The Nasdaq Stock Market. Corporate Governance Requirements.” Nasdaq Listing Center. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://listingcenter.nasdaq.com/rulebook/nasdaq/rules/nasdaq-5600-series#:~:text=These%20requirements%20include%20rules%20relating%20to%20a%20Company%27s,party%20transactions%3B%20and%20shareholder%20approval%2C%20including%20voting%20rights.

[43] Werschkul, Ben. “Companies Test out Different Ways to Talk about ESG without Saying ‘ESG.’” Yahoo Finance, February 4, 2024. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/companies-test-out-different-ways-to-talk-about-esg-without-saying-esg-125007682.html.

[44] Armstrong, Brian. “Coinbase Is a Mission Focused Company.” Coinbase, September 27, 2020. https://www.coinbase.com/blog/coinbase-is-a-mission-focused-company. ; Pichai, Sundar. “Building for Our AI Future.” Google, April 18, 2024. https://blog.google/inside-google/company-announcements/building-ai-future-april-2024/

[45] Copland, James R. “Index Funds Have Too Much Voting Power: A Proposal for Reform.” Manhattan Institute, January 2024. https://manhattan.institute/article/index-funds-have-too-much-voting-power-a-proposal-for-reform.

[46] Lewis, C. S. Mere Christianity. New York: HarperCollins, 2001 [1952]; 28-29.