In a recent Vox column, Matt Yglesias offers an extensive critique of former New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley’s controversial article. Dudley has argued that the Fed should “refuse to play along” with President Trump’s trade war and conduct monetary policy to reduce the president’s odds of re-election. Yglesias rightly condemns Dudley’s proposal as venturing into “fairly outrageous territory.” But he fails to make a principled case for independent monetary policy.

Instead, Yglesias focuses on what he views as the real threat posed by the Fed both historically and today — that it sits idly by while Republicans run up huge deficits yet stonewall Democrats when they try to enact big-ticket policies. “Historically, disciplinary monetary policy has been used by central banks to constrain the left,” Yglesias argues. Throughout its history, the Fed has let “Republicans explode the deficit” with tax cuts, then “pressured Democrats to narrow it.”

This partisan deficit hawking, he argues, is actually “the most dangerous idea in central banking.” Yglesias concludes that progressives should start preparing for a “political fight” with the Fed the next time a Democrat takes the Oval Office. “The real risk of central bank meddling is not during the Trump administration,” he argues, “but during the next administration.”

Yglesias uses Greenspan’s tenure as an example. In 1993, he writes, Greenspan “pressured” President Clinton to cut the deficit. Greenspan’s pressure, he argues, prevented Clinton from passing any signature progressive reforms. Yet, when George W. Bush was elected, “Greenspan changed his view on deficits.”

But Greenspan’s emphasis on deficit reduction wasn’t necessarily partisan or unwarranted. His advice came at the tail end of a decade of massive spending growth where the debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 37.17 to 64.67 percent. Yglesias conveniently ignores the fact that Greenspan pressured Presidents Reagan and George H. W. Bush to cut the deficit as well, beginning as early as 1988. This helped influence President Bush to break his famous “read my lips” promise and raise taxes in 1990.

Nor was Greenspan’s “reversal” on the deficit-cutting issue in the early 2000s necessarily motivated by partisan politics. By Q2 2001, the debt-to-GDP ratio had fallen to 54.04 percent. It’s true that deficits exploded under George W. Bush. But, at 61 percent in 2006 when Greenspan left office, debt-to-GDP was still less than had been at the height of the Clinton years. And, contrary to Yglesias’s assertion, it was not the Bush tax cuts that fueled the deficits. It was a huge increase in spending — just as it had been under Reagan.

There are many reasons to demur Greenspan’s tenure as Fed chair. But Yglesias’s claim that he “meddled” for overtly partisan reasons is unfounded.

His overarching claim, that the long history of Fed meddling has tended to support Republicans, is also problematic. There are plenty of examples of central banks meddling in ways that help Democrats, as well.

During World War I, at the behest of President Woodrow Wilson, the Fed helped keep interest rates low and provided preferential discount rates to banks that purchased war bonds. It is no surprise that this period saw the highest inflation rates in the Fed’s history.

Similarly, the Fed accommodated rising deficits under President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II by pegging Treasury rates at a low level. The Fed maintained this policy for another six years into Harry Truman’s presidency, when the Treasury-Fed Accord in 1951 separated monetary policy from government debt management.

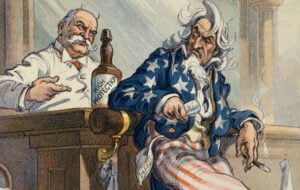

President Lyndon Johnson successfully pressured then Fed Chair William McChesney Martin to keep interest rates low to help finance the Vietnam War and Great Society programs. Johnson reportedly went so far as to verbally assault Martin at his Texas ranch, yelling, “Boys are dying in Vietnam, and Bill Martin doesn’t care!” Martin obliged, setting the stage for the Great Inflation of the 1960s and ’70s.

Fed meddling is a real problem, to be sure. But, contrary to Yglesias’s claim, it has tended to accommodate deficits under both Democrats and Republicans.

The solution to Fed meddling — be it in support of Democrats or Republicans — is to establish a strict separation of money and state. Unfortunately, that’s not what Yglesias argues. His issue with the Fed isn’t that it is partisan, but that it isn’t partisan enough. He wants the Fed to help progressives finance their preferred policies.

The best way to avoid accusations of “partisan meddling” isn’t by demanding that progressives prepare for a “political fight” with the Fed to make it partisan in their favor. It’s to make the Fed more independent of politics. And the best way for the Fed to prove its independence would be to embrace a clear and binding rule for monetary policy that it can be held accountable no matter which party is in power.

Progressives like Yglesias recognize the danger of money in politics. They should consider the danger of politics in money, as well. And not just when it suits their interests.