The last few weeks have seen a spike in commentaries surrounding modern monetary theory (MMT). A column by Prof. Stephanie Kelton, Andres Bernal, and Greg Carlock at Huffington Post and an endorsement from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) have triggered negative responses by a number of reputable economists. George Selgin, Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, and Ken Rogoff (just to name a few) have all expressed concerns (to put it mildly) about the implications of applying MMT.

A common thread in these (and other) responses is that it is not clear what MMT really stands for. Advocates of MMT seem to use conventional terms in unconventional ways, and that creates confusion. On top of this, what exactly MMT means changes as time goes by, thereby adding frustration to confusion.

At its core, MMT maintains that a government cannot go broke as long as it can issue its own currency. Large fiscal deficits can be paid for by “printing money” (or, more technically, monetizing deficits). Standard monetary theory maintains that such a policy causes inflation. MMT, in contrast, holds that such a policy is not inflationary, because there are idle resources.

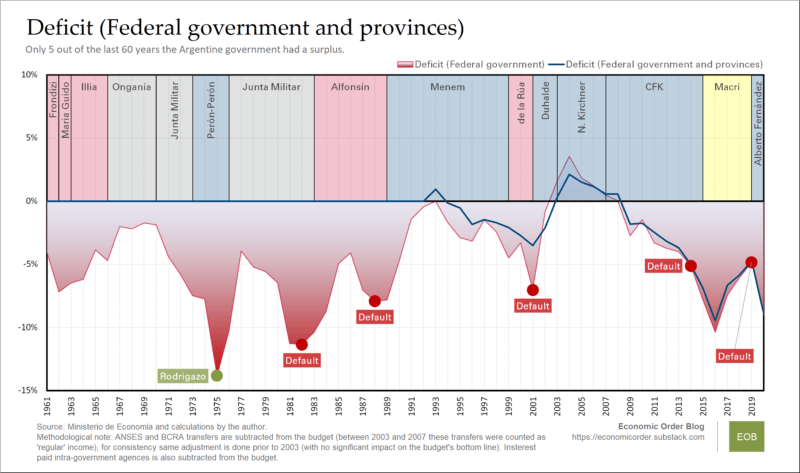

Can governments run large fiscal deficits financed with new money without generating significant inflation? The experience of Argentina calls this view into doubt. As shown in the figure below, Argentina has had a chronic fiscal deficit for the last 50 years (with the exception of a few years after the 2001 crisis). The red area shows the consolidated deficit (all levels of government) as a share of nominal income. The blue line (starting in 1993) shows only the deficit at the federal level, also as a share of nominal income. The depicted chronic deficits have resulted in numerous problems, such as inflation, sovereign-debt defaults, and currency crises.

Like MMT advocates, Argentinian policy makers seem to think that deficits don’t matter and, by implication, that the budget constraint is not really binding. What are some of the effects of this deficit policy? There have been at least four sovereign-debt defaults (the yellow dots). A serious crisis, known as the “Rodrigazo,” arguably contributed to the social environment that led to the military government (junta militar) between 1976 and 1983. Argentina experienced hyperinflation in the late 1980s and early 1990s and a great depression in 2001. It has experienced stagflation since 2011. In fact, other than the 1990s, when it had a currency board, Argentina has suffered high inflation rates over the entire period. Meanwhile, the poverty rate (which fiscal deficits are intended to reduce) remains high.

It is hard to imagine how an MMT advocate would explain away the experience of Argentina. Perhaps the requirement that a country can issue its own currency is, in fact, a requirement that a country can issue debt in its own currency. That would explain why Argentinian outcomes differ from those predicted by MMT. However, it is hard to imagine that a country would be able to issue debt in its own currency for long if it were engaged in deficit spending to the extent MMT advocates propose. In other words, that explanation — while preserving the integrity of the original argument — undermines its practical application.

Alternatively, MMT advocates might fall back on the inflation constraint, which they acknowledge when pressed. If inflation picks up, they say, then countermeasures will be adopted. Again, we have an explanation that undermines the practical application of MMT. But it is even worse than that. Argentina did not adopt countermeasures. In suggesting that countries could just adopt countermeasures when inflation picks up, MMT fails to account for political incentives. Its advocates confuse the the possible with the probable.

Argentina’s experience gives us reason to doubt the practical relevance of MMT. In downplaying the costs of deficit spending and monetizing deficits, advocates of MMT enable political actors — even those with the best of intentions — to pursue policies that will ultimately reduce the living standards of the least well off.