Average American’s Cost of Living Falls

This research brief examines current trends in American households’ cost of living. We begin by looking at trends in inflation compared with wages. Next, we look at changes in costs faced by households and in product or service categories. Finally, we provide data that allow you to calculate the purchasing power of a dollar over several decades.

Inflation slowed during 2015, with the CPI increasing by only 0.5 percent for the 12 months ending Nov. 30, 2015. This figure actually represents a small year-end uptick, as 12-month changes earlier in the year were zero or even negative. Low inflation is being driven by cheap oil and a strong U.S. dollar. Officially, the Federal Reserve has expressed confidence that inflation will approach its 2 percent target in 2016, although some Fed policy makers have expressed concern that inflation may stay below that level.

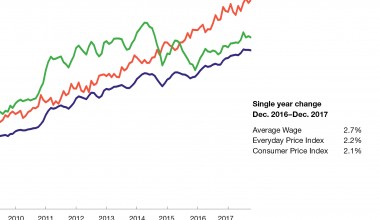

Chart 1 compares changes in the CPI with wages over one year and since 2009. Wages outpaced inflation in 2015, after moving largely in tandem since the end of the Great Recession in June 2009.

Overall, the past decade has seen very limited inflation, which has not significantly reduced the purchasing power of typical earnings and investments.

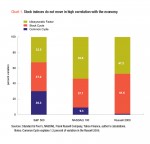

Table 1 compares the Consumer Price Index, which is the broad price index issued by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, with AIER’s Everyday Price Index, a narrower index of the most common everyday expenses. It provides examples of costs of living for three types of typical American households, which we are calling Urban Renter, Retired Couple, and Young Family. These examples show how different mixes of goods and services interact to yield different changes in the cost of living over time.

How the EPI and CPI compare

The EPI excludes big-ticket items such as housing, cars, appliances, and electronics as well as simpler, infrequent purchases such as clothing and professional services (e.g., legal and financial).

Since the EPI weights gas more heavily than the CPI, it shows higher inflation over this period. Even with recent declines, the price of gas has increased 70 percent since January 2000, a higher rate than the overall CPI. Utilities, gas, prescription drugs, cable, and tobacco prices all act to buoy everyday prices as measured by the EPI. By excluding items with lower-than-average inflation (apparel, electronics, and appliances) and overweighting items with higher-than-average inflation, the EPI’s inflation measure has outpaced the CPI since 2000.

Urban Renter

The Urban Renter profile shows modestly higher inflation than the CPI and lower inflation than the EPI. This category starts with the EPI profile but excludes gasoline and certain utilities. The Urban Renter profile adds shelter (rent) and airfare. It over-weights food purchased at restaurants, alcohol, and public transportation. Lower expenditures on energy mean that the Urban Renter saw higher inflation in 2015 than our other examples.

Since 2000, the Urban Renter has faced about 49 percent inflation, driven largely by rents (+48 percent since January 2000). Urban Renter inflation is pushed higher by spending more on food in restaurants, a category that has increased 55 percent since January 2000, and on intracity public transportation, which has increased in price 77 percent since January 2000.

Retired Couple

The Retired Couple profile shows higher inflation than reported in the CPI but lower than the EPI. This profile assigns less weight to expenses for food at a restaurant and gas and greater weight to prescription drugs and medical-care services. The heavier-than-normal weight on medical services is the largest driver of inflation for the Retired Couple.

Prescription drug prices have increased 72 percent since January 2000, while prices of medical-care services have increased 85 percent. These increases have become burdensome for families that spend an outsize portion of their budgets on health care. In this example the Retired Couple uses gas for heating and utilities, which has helped keep inflation in check, as gas heating prices increased less than oil or kerosene during this period.

Young Family

The Young Family has experienced much higher inflation than shown in the CPI and EPI over the past 15 years, despite a falling cost of living in 2015 due to lower gasoline prices. The profile for the Young Family may be indicative of the price pressures that many middle class Americans have felt.

The Young Family profile starts with the EPI but excludes certain utilities and tobacco. In this profile we assign a greater weight to purchases of educational supplies, college tuition, child care, and fuel oil. This profile is meant to represent a family with young or teenage children—one that has been saving for college.

There are several extraordinary price increases that have caused the Young Family to experience high aggregate inflation. Prices of educational books and supplies have increased 141 percent, and college tuition and fees have increased 146 percent since January 2000. Child care and nursery school prices have increased 83 percent over this time.

Imagine parents that started saving for college and paying for child care in 2000 when their child was young. Even if they are not yet paying for college, they must incorporate the extraordinary price increases for education into their budgeting. Inflation has severely affected families that need to assign a disproportionate amount of their income to child care and college tuition or college savings.

As Table 2 shows, prices of many CPI components (as in other indices) fell in 2015, led by price drops for products related to petroleum and electronics. Products and services related to education had some of the year’s largest price increases.

Since 2000, prices for tobacco and education-related products and services have more than doubled. Among other items logging the largest price increases in the past decade-and-a-half are water and sewer utilities, propane and kerosene, and gasoline and car insurance. As is commonly the case with technology goods over time, those prices have decreased dramatically since 2000.

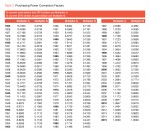

Table 3 provides a simple way to convert values from the past into their equivalent value today (or vice versa). To convert a value from a particular year to its 2015 equivalent, multiply the original price by the conversion factor, Multiplier A shown in the table for the appropriate year.

For instance, if you want to know whether the value of your house has kept pace with inflation, multiply the price of the house by the Multiplier A factor shown for the year you purchased it.

Example: A house was purchased in 1965 for $25,000. Adjusting for price inflation, this price in terms of 2015 dollars is $25,000 x 7.4869 = $187,173. This is approximately how much the house would have to sell for today just to keep up with price inflation.

To convert 2015 dollars into past dollars, multiply today’s dollar amount by the conversion factor, Multiplier B shown in the table for the appropriate year.

Example: If the price of a movie ticket is about $10 today, what was the constant-dollar equivalent in 1974? Today’s $10 purchase price in terms of 1974 dollars is $10 x 0.2170 = $2.17. )

[pdf-embedder url=”https://www.aier.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/RB_February2016_COLA.pdf“]