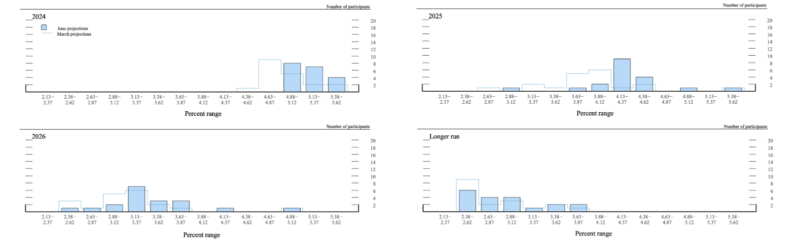

As anticipated, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted to hold its federal funds rate target in the 5.25 to 5.5 percent range on Tuesday. FOMC members also revised their forward guidance for the future path of interest rates. Back in March, the median FOMC member projected the midpoint of the federal funds rate target range would fall to 4.6 percent this year, equivalent to three 25-basis-point cuts. Now, the median FOMC member projects it will fall to just 5.1 percent, equivalent to just one 25-basis-point cut.

The FOMC’s plan to hold rates higher for longer is not limited to 2024. The median FOMC member now projects the federal funds rate will be 4.1 percent in 2025, compared with the earlier projection of 3.9 percent. The median FOMC member also revised up the longer run federal funds rate projection, from 2.6 percent to 2.8 percent.

Why have FOMC members revised up their projections for the federal funds rate? There are likely two reasons. First, FOMC members seem to believe that the long run neutral real rate of interest — what economists call r* — is higher than previously thought. Second, they now think inflation will decline more slowly. Consequently, they will take longer to cut rates, and not cut rates quite as far.

Gov. Christopher Waller offered Some Thoughts on r* at the Reykjavik Economic Conference last month. In the talk, Waller paid specific attention to fiscal policy, noting that r* will rise “if the growth in the supply of US Treasuries begins to outstrip demand.”

It is probably not news to many people that the US is on an unsustainable fiscal path. The latest outlook from the Congressional Budget Office paints a challenging picture of the future, with debt expected to grow at an unprecedentedly high rate for an economy at full employment and not involved in a major war.

All of these financing pressures may contribute to a rise in r* in coming years, but only time will tell how large a factor the U.S. fiscal position will be in affecting r*.

If r* will be higher than previously expected in the long run, then the Fed will not need to cut rates as far as it had previously thought necessary when returning policy to a neutral stance.

The latest projections suggest Waller is not alone in thinking fiscal policy will push up the long run neutral real rate of interest. The median FOMC member increased his or her projection of the nominal federal funds rate in the longer run, while leaving his or her projection of inflation in the longer run at 2.0 percent. Taken together, those changes imply an increase in the projected long-run neutral real rate of interest.

FOMC members also think inflation will decline more slowly. That’s partly due to the sudden resurgence in inflation in 2024:Q1. The median FOMC member now thinks the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, which is the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, will grow 2.6 percent this year, compared with the 2.4 percent projected back in March. The median FOMC member now projects core PCE inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, at 2.8 percent in 2024. In March, the median FOMC member had projected just 2.6 percent core PCE inflation this year.

It is not merely that the earlier inflation has caused FOMC members to revise upward their projections of inflation. They also think inflation will be higher in the future. The median FOMC member now projects 2.3 percent headline and core PCE inflation in 2025, compared with earlier projections of 2.2 percent.

The decision to hold rates higher for longer is understandable. FOMC members are not satisfied with the pace of disinflation so far and intend to keep policy tighter in the near term to ensure inflation eventually returns to target. At the same time, they believe fiscal policy (and perhaps other factors) are pushing up the long-run neutral real interest rate, meaning they will not need to cut rates as far when the time to adopt a neutral policy stance eventually comes.

Of course, to say that the FOMC’s intended policy path is understandable does not imply that it is ideal. The latest inflation data, released this morning, showed basically no change in the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) over the last month (zero inflation month-over-month). Core CPI inflation was just 2.0 percent in May. Perhaps inflation will pick back up somewhat in the months ahead. But there is little reason to think inflation will not be back down to the FOMC’s two-percent target in 2025.

The big risk over the next two quarters is that the FOMC holds its target rate too high for too long. Just as the FOMC was slow to adjust policy when inflation surged in late 2021, it will be slow to adjust policy as inflation returns to and falls below its target in 2024. With its nominal interest rate target fixed firmly at 5.25 to 5.0 percent, falling inflation pushes the FOMC’s implicit real federal funds rate target higher. Left unchecked, that will cause economic activity to slow and unemployment to rise.